|

|

Research Findings

The Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity Landscape

|

下部組織のCybersecurityの重大な景色

|

Today’s Outlook on Cybersecurity Threats More Bleak than in 2013

|

2013年により寒冷なCybersecurityの脅威の今日の展望

|

|

Defending against cyber-attacks represents a perpetual battle for critical infrastructure organizations facing an increasingly dangerous threat landscape. In fact, 31% of security professionals working at critical infrastructure organizations believe that the threat landscape today is much worse than it was two years ago, while another 36% say it is somewhat worse (see Figure 1).

|

に対して防御は表すますます危ない脅威の景色に直面する重大な下部組織の組織のための永遠の戦いをcyber攻撃する。 実際は、重大な下部組織の組織で働いている保証専門家の31%はもう36%は言うがそれが前に2年だったより大いに悪い脅威の景色が今日ことを信じる、それは幾分より悪い(図1を見なさい)。

|

|

It is interesting to note that ESG asked this same question in its 2010 research project,1 and it produced strikingly similar results—68% of respondents said that the threat landscape was worse in 2010 compared with 2008. Clearly, the threat landscape is getting more hazardous on an annual basis with no letup in sight. ESG finds this data particularly troubling. U.S. citizens depend upon critical infrastructure organizations for the basic necessities of modern society like food, water, fuel, and telecommunications services. Given the increasingly dangerous threat landscape, critical infrastructure organizations are tasked with maintaining important everyday services and defending their networks from a growing army of cyber-criminals, hacktivists, and nation state actors.

|

、1にESGがこれに2010研究計画の同じ質問をしたこと注意することは興味深い そしてそれは脅威の景色が2008年と比較された2010でより悪かったと著しく被告の同じような結果68%を言った作り出した。 明らかに、脅威の景色は視力のletup無しで毎年より危険になっている。 ESGはこのデータを特に悩むことを見つける。 米国. 市民は食糧、水、燃料およびテレコミュニケーションサービスのような現代社会の基本的な必要のための重大な下部組織の組織に依存する。 ますます危ない脅威の景色を与えられて、重大な下部組織の組織は重要な毎日サービスを維持し、cyber犯罪者、hacktivistsおよび国家州俳優の成長する軍隊からのネットワークを守ることと任せられる。

|

|

Note1: Source: ESG Research Report, Assessing Cyber Supply Chain Security Vulnerabilities Within the U.S. Critical Infrastructure, November 2010.

|

Note1: 源: 米国内のCyberのサプライチェーンのセキュリティーの脆弱性を査定するESGの研究のレポート。 重大な下部組織、2010年11月。

|

|

These beliefs about the increasingly dangerous threat landscape go beyond opinions alone as many critical infrastructure organizations face constant cyber-attacks. A majority (68%) of critical infrastructure organizations experienced a security incident over the past two years, with nearly one-third (31%) experiencing a system compromise as a result of a generic attack (i.e., virus, Trojan, etc.) brought in by a user’s system, 26% reporting a data breach due to lost/stolen equipment, and 25% of critical infrastructure organizations suffering some type of insider attack (see Figure 2). Alarmingly, more than half (53%) of critical infrastructure organizations have dealt with at least two of these security incidents since 2013.

|

これらのますます危ない脅威の景色についての確信は単独で意見を越えて一定した表面がcyber攻撃する同様に多くの重大な下部組織の組織行く。 重大な下部組織の組織の大半(68%)はユーザーのシステムによって、無くなったか盗まれた装置のためにデータ違反を報告する26%持って来られた経験する一般的な攻撃(すなわち、ウイルス、トロイ人、等)の結果としてシステム妥協をほぼ3分の1 (31%)およびある種の部内者の攻撃に苦しむ重大な下部組織の組織の25%との過去の2年にわたる保証事件を、経験した(図2を見なさい)。 驚くほどに、重大な下部組織の組織の半分(53%)より多くは2013年以来のこれらの保証事件の少なくとも2を取扱った。

|

|

Security incidents always come with ramifications associated with time and money. For example, nearly half (47%) of cybersecurity professionals working at critical infrastructure organizations claim that security incidents required significant IT time/personnel for remediation. While this places an unexpected burden on IT and cybersecurity groups, other consequences related to security incidents were far more ominous—36% say that security incidents led to the disruption of a critical business process or business operations, 36% claim that security incidents resulted in the disruption of business applications or IT systems availability, and 32% report that security incidents led to a breach of confidential data (see Figure 3).

|

保証事件は時間およびお金と関連付けられる分枝と常に来る。 例えば保証事件が重要それを治療の時間か人員要求したことを、重大な下部組織の組織で働いているcybersecurityの専門家のほぼ半分(47%)は主張する。 これがそれおよびcybersecurityのグループに予想外の重荷を置く間、保証事件と関連していた他の結果は保証事件がビジネス・アプリケーションまたはそれの中断でシステム可用性起因した、および保証事件が機密データの違反に導いた32%のレポートをだったこと保証事件が重大なビジネス過程または運営業務の中断をもたらしたことはるかに不吉36%言う、36%の要求を(図3を見なさい)。

|

|

This data should be cause for concern since a successful cyber-attack on critical infrastructure organizations’ applications and processes could result in the disruption of electrical power, health care services, or the distribution of food. Thus, these issues could have a devastating impact on U.S. citizens and national security.

|

このデータは成功したの重大な下部組織の組織ので」適用cyber攻撃し、プロセスが電力の中断、食糧のヘルスケアサービス、または配分で起因できるので不安の原因べきである。 従って、これらの問題に米国の計り知れない影響があることができる。 市民および国家安全保障。

|

Cybersecurity at Critical Infrastructure Organizations

|

重大な下部組織の組織のCybersecurity

|

|

Do critical infrastructure organizations believe they have the right cybersecurity policies, processes, skills, and technologies to address the increasingly dangerous threat landscape? The results of that inquiry are mixed at best. On the positive side, 37% rate their organizations’ cybersecurity policies, processes, and technologies as excellent and capable of addressing almost all of today’s threats. It is worth noting that the overall ratings have improved since 2010 (see Table 1). While this improvement is noteworthy, 10% of critical infrastructure security professionals still rate their organization as fair or poor.

|

重大な下部組織の組織は右のcybersecurityの方針、プロセス、技術および技術をますます危ない脅威の景色に演説する持つために信じるか。 その照会の結果は精々混合される。 今日の脅威ほとんどすべてに演説する優秀、ことができる肯定的な側面、37%率彼らの組織の」 cybersecurityの方針、プロセスおよび技術。 全面的な評価が2010年以来改良していたことは無益である(表1を見なさい)。 この改善が顕著な間、重大な下部組織の保証専門家の10%はまだ公平ように彼らの構成か貧乏人を評価する。

|

|

Being able to deal with most threats may be an improvement from 2010, but it is still not enough. This is especially true given the fact that the threat landscape has grown more difficult at the same time. Critical infrastructure organizations are making progress, but defensive measures are not progressing at the same pace as the offensive capabilities of today’s cyber-adversaries and this risk gap leaves all U.S. citizens vulnerable.

|

ほとんどの脅威を取扱える2010年からの改善であるまだ十分ではない。 脅威の景色が同時により困難に育ったという事実があるこれは言うことができる。 重大な下部組織の組織は進歩をしているが、今日のcyber敵およびこの危険のギャップの攻撃的な機能がすべての米国を去ると防御手段は同じペースで進歩していない。 傷つきやすい市民。

|

Table 1. Respondents Rate Organization’s Cybersecurity Policies

|

Given the national security implications of critical infrastructure, it is not surprising that cybersecurity risk has become an increasingly important board room issue over the past five years. Nearly half (45%) of cybersecurity professionals today rate their organization’s executive management team as excellent, while only 25% rated them as highly in 2010 (see Table 2). Alternatively, 10% rate the executive management team’s cybersecurity commitment as fair or poor in 2015, where 23% rated them so in 2010. These results are somewhat expected given the visible and damaging data breaches of the past few years. Critical infrastructure cybersecurity is also top of mind in Washington with legislators, civilian agencies, and the executive branch. For example, the 2014 National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) cybersecurity framework (CSF) was driven by an executive order and is intended to help critical infrastructure organizations measure and manage cyber-risk more effectively. As a result of all of this cybersecurity activity, corporate boards are much more engaged in cybersecurity than they were in the past, but whether they are doing enough or investing in the right areas is still questionable.

|

重大な下部組織の国家安全保障の含意を与えられて、それはcybersecurityの危険が過去5年にわたるますます重要な会議室問題になっても不思議ではない。 25%だけは非常にとして2010年にそれらを評価したが、cybersecurityの専門家のほぼ半分(45%)は優秀ように今日彼らの構成の管理の経営陣を評価する(表2を見なさい)。 また23%が2010年にそれらをそう評価したところ、10%の率公平管理の経営陣のcybersecurityの責任か2015年に貧乏人。 これらの結果は幾分過去数年間の目に見え、有害なデータ違反を与えられて期待される。 重大な下部組織のcybersecurityは立法者、一般市民代理店および行政機関が付いているワシントン州の心のまた上である。 例えば、2014年国立標準技術研究所(NIST)のcybersecurityフレームワーク(CSF)は政令によって運転され、重大な下部組織の組織の測定を助け、cyber危険をもっと効果的に管理するように意図されている。 このcybersecurityの活動すべての結果として、団体板はcybersecurityで大いにもっと右の区域に投資してまだ不審があることを以前あったが、かどうか十分をまたはするか、より従事している。

|

Table 2. Respondents Rate Organization’s Executive Management Team with Regard to Cybersecurity Initiatives

|

Critical infrastructure organizations are modifying their cybersecurity strategies for a number of reasons. For example, 37% say that their organization’s infosec strategy is driven by the need to support new IT initiatives with strong security best practices. This likely refers to IT projects for process automation that include Internet of Things (IoT) technologies. IoT projects can bolster productivity, but they also introduce new vulnerabilities and thus the need for additional security controls. Furthermore, 37% point to protecting sensitive customer data confidentiality and integrity, and 36% call out the need to protect internal data confidentiality and integrity (see Figure 4). These are certainly worthwhile goals, but ESG was surprised that only 22% of critical infrastructures say that their information security strategy is being driven by preventing/detecting targeted attacks and sophisticated malware threats. After all, 67% of security professionals believe that the threat landscape is more dangerous today than it was two years ago, and 68% of organizations have suffered at least one security incident over the past two years. Since critical infrastructure organizations are under constant attack, ESG feels strongly that CISOs in these organizations should be assessing whether they are doing enough to prevent, detect, and respond to modern cyber-attacks.

|

重大な下部組織の組織はいくつかの理由のためのcybersecurityの作戦を変更している。 例えば、37%は構成のinfosecの作戦が新しいそれを支える必要性によって強いセキュリティの最良の方法の率先運転されると言う。 この本当らしいそれを事(IoT)の技術のインターネットが含まれているプロセス・オートメーションのためのプロジェクト示す。 IoTのプロジェクトは生産性をささえることができるがまた付加的な機密管理のための新しい脆弱性そしてこうして必要性をもたらす。 なお、敏感な顧客データ機密性のおよび完全性保護への37%ポイント、および36%は内部データの機密性および完全性を保護する必要性を出動させる(図4を見なさい)。 これらは確かに価値がある目的であるが、情報セキュリティの作戦が目標とされた攻撃および複雑にされたmalwareの脅威をことを防ぐか、または検出することによって運転されていると重大な下部組織の22%だけが言うことESGは驚いた。 結局、保証専門家の67%はそれが前に2年だった、組織の68%は過去の2年にわたる少なくとも1つの保証事件に苦しんだより脅威の景色がより危ない今日であることを信じ。 重大な下部組織の組織が一定した攻撃の下にあるので、ESGはこれらの組織のCISOsが、検出するために防ぐには十分をし、現代に答えることはcyber攻撃するかどうか査定するべきであることに強く感じる。

|

Cyber Supply Chain Security

|

Cyberのサプライチェーンの保証

|

|

Like many other areas of cybersecurity, cyber supply chain security is growing increasingly cumbersome. In fact, 60% of security professionals say that cyber supply chain security has become either much more difficult (17%) or somewhat more difficult (43%) over the last two years (see Figure 5).

|

cybersecurityの他の多くの地域のように、cyberのサプライチェーンの保証はますます扱いにくく育っている。 実際は、保証専門家の60%はcyberのサプライチェーンの保証がはるかに困難に(17%)または最後の2年にわたって幾分より困難に(43%)なったと言う(図5を見なさい)。

|

|

Why has cyber supply chain security become more difficult? Forty-four percent claim that their organizations have implemented new types of IT initiatives (i.e., cloud computing, mobile applications, IoT, big data analytics projects, etc.), which have increased the cyber supply chain attack surface; 39% say that their organization has more IT suppliers than it did two years ago; and 36% state that their organization has consolidated IT and operational technology security, which has increased infosec complexity (see Figure 6).

|

サプライチェーンの保証はなぜcyberのより困難になったか。 組織がそれの新型をcyberのサプライチェーンの攻撃の表面を高めた率先(すなわち、雲の計算、移動式適用、IoT、大きいデータanalyticsのプロジェクト、等)実行したこと四十四%の要求、; 39%は構成に多くがそれ製造者あるとよりそれした2年言う前に; そして構成がそれおよびinfosecの複雑さを(高めた操作上の技術の保証を強化したこと36%の国家は、図6を見る)。

|

|

This data is indicative of the state of IT today. The fact is that IT applications, infrastructure, and products are evolving at an increasing pace, driving dynamic changes on a constant basis and increasing the overall cyber supply chain attack surface. Over-burdened CISOs and infosec staff find it difficult to keep up with dynamic cyber supply chain security changes, leading to escalating risks.

|

このデータはそれの状態を今日表している。 事実は増加するペースで適用、下部組織およびプロダクト展開して、一定した基礎の動的変更を運転したり全面的なcyberのサプライチェーンの攻撃の表面を高めていることである。 過度に負わせられたCISOsおよびinfosecのスタッフの発見増大の危険をもたらす動的cyberのサプライチェーンのセキュリティの変更に遅れずについていくこと困難なそれ。

|

Cyber Supply Chain Security and Information Technology

|

Cyberのサプライチェーンの保証および情報技術

|

|

Cybersecurity protection begins with a highly secure IT infrastructure. Networking equipment, servers, endpoints, and IoT devices should be “hardened” before they are deployed on production networks. Access to all IT systems must adhere to the principle of “least privilege” and be safeguarded with role-based access controls that are audited on a continuous or regular basis. IT administration must be segmented through “separation of duties.” Networks must be scanned regularly and software patches applied rapidly. All security controls must be monitored constantly.

|

Cybersecurityの保護は非常に安全のからそれを下部組織始める。 生産ネットワークで配置される前にネットワーク機器、サーバー、終点およびIoT装置は「」堅くなるべきである。 「最少特権」の原則に連続的か規則的な基礎で監査されるシステム付着させ、役割基づかせていたアクセス制御と保護されなければならないすべてへのアクセス。 それは「義務の分離によって管理区分されなければならない」。 ネットワークは急速に加えられるソフトウェアパッチ規則的にスキャンされなければ。 すべての機密管理は絶えず監視されなければならない。

|

|

These principles are often applied to internal applications, networks, and systems but may not be as stringent with regard to the extensive network of IT suppliers, service providers, business partners, contractors, and customers that make up the cyber supply chain. As a review, the cyber supply chain is defined as:

|

これらの主義は頻繁に内部適用、ネットワークおよびシステムに適用されるが、それの広汎なネットワークに関して厳しいように製造者、サービス・プロバイダ、共同経営者、建築業者およびcyberのサプライチェーンを構成する顧客ではないことができる。 検討と、cyberのサプライチェーンは次のように定義される:

|

|

The entire set of key actors involved with/using cyber infrastructure: system end-users, policy makers, acquisition specialists, system integrators, network providers, and software/hardware suppliers. The organizational and process-level interactions between these constituencies are used to plan, build, manage, maintain, and defend the cyber infrastructure.”

|

にかかわるか、またはcyberの下部組織を使用している主俳優の全体のセット: システムエンドユーザー、政策当局者、獲得の専門家、システム・インテグレーター、ネットワークプロバイダおよびソフトウェアまたはハードウェア製造者。 これらの選挙区民間の組織およびプロセスレベルの相互作用が使用されているcyberの下部組織を計画し、造り、経営し、維持し、守るのに」。

|

|

To explore the many facets of cyber supply chain security, this report examines:

|

cyberのサプライチェーンの保証の多くの面を探検するためには、このレポートは検査する:

|

|

The relationships between critical infrastructure organizations and their IT vendors (i.e., hardware, software, and services suppliers as well as system integrators, channel partners, and distributors).

|

重大な下部組織の組織間の関係および彼等のそれ売り手(システム・インテグレーター、チャネルパートナーおよびディストリビューターと同様、すなわち、ハードウェア、ソフトウェアおよびサービス製造者)。

|

|

The security processes and oversight applied to critical infrastructure organizations’ software that is produced by internal developers and third parties.

|

保証プロセスおよび手落ちは重大な下部組織の組織に」内部開発者および第三者によって作り出されるソフトウェア適用した。

|

|

Cybersecurity processes and controls in instances where critical infrastructure organizations are either providing third parties (i.e., suppliers, customers, and business partners) with access to IT applications and services, or are consuming IT applications and services provided by third parties (note: throughout this report, this is often referred to as “external IT”).

|

重大な下部組織の組織がそれへのアクセスを用いるどちらかの提供の第三者(すなわち、製造者、顧客および共同経営者)適用およびサービスである例のCybersecurityプロセスそして制御は、またはそれを第三者(ノートによって提供される適用およびサービス消費している: このレポート中、これは頻繁に「外面とそれ」言われる)。

|

Cyber Supply Chain Security and IT Suppliers

|

Cyberのサプライチェーンの保証およびそれ製造者

|

|

Cybersecurity product vendors, service providers, and resellers are an essential part of the overall cyber supply chain. Accordingly, their cybersecurity policies and processes can have a profound downstream impact on their customers, their customers’ customers, and so on. Given this situation, critical infrastructure organizations often include cybersecurity considerations when making IT procurement decisions.

|

Cybersecurityプロダクト売り手、サービス・プロバイダおよび転売者は全面的なcyberのサプライチェーンの必須の部分である。 したがって、cybersecurityの方針およびプロセスは顧客、顧客の」顧客の深遠な下流の影響を、およびそう有することができる。 この状態を与えられて、重大な下部組織の組織は頻繁にそれに調達の決定をするときcybersecurityの考察を含んでいる。

|

|

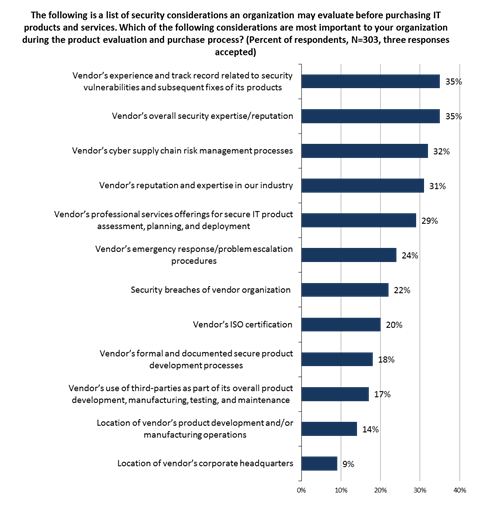

Just what types of cybersecurity considerations are most important? More than one-third (35%) of organizations consider their vendors’ experience and track record related to security vulnerabilities and subsequent fixes. In other words, critical infrastructure organizations are judging vendors by the quality of their software and their responsiveness in fixing software vulnerabilities when they do arise. Another 35% consider their vendors’ overall security expertise and reputation. Close behind, 32% consider their vendors’ cyber supply chain risk management processes, while 31% contemplate their vendors’ reputation and industry expertise (see Figure 7).

|

ちょうどどのようなcybersecurityの考察をほとんどは重要あるか。 組織の3分の1以上(35%)売り手の」経験およびセキュリティーの脆弱性およびそれに続く苦境と関連している実績考慮する。 すなわち、重大な下部組織の組織は固定ソフトウェア脆弱性のソフトウェアそして敏感さの質によって起こるとき売り手を判断している。 もう35%は売り手を」全面的な保証専門知識および評判と考慮する。 後ろ閉めなさい、32%は31%は売り手」の評判および企業の専門知識熟視するが、売り手を」 cyberサプライチェーンリスク管理プロセス考慮する(図7を見なさい)。

|

|

Clearly, critical infrastructure organizations have a number of cybersecurity considerations regarding their IT vendors, but many of these concerns, such as vendor reputation and expertise, remain subjective. To counterbalance these soft considerations, CISOs should really establish a list of objective metrics such as the number of CVEs associated with specific ISV applications and the average timeframe between vulnerability disclosure and security patch releases. These types of metrics can be helpful when comparing one IT vendor’s security proficiency against another’s.

|

明らかに、重大な下部組織の組織に彼等のに関するいくつかのcybersecurityの考察がそれ売り手あるが、これらの心配の多数は、売り手の評判および専門知識のような、主観的に残る。 これらの柔らかい考察を相殺するためには、CISOsは実際に脆弱性の発表と保証パッチ解放間の特定のISVの適用そして平均時間枠と関連付けられるCVEsの数のような客観的な測定基準のリストを確立するべきである。 者それを売り手の保証実力別に対して比較するときこれらのタイプの測定基準は有用である場合もある。

|

|

Cyber supply chain security best practices dictate that organizations assess the security processes, procedures, and technology safeguards used by all of their IT suppliers. In order to measure the cybersecurity practices of IT vendors, some critical infrastructure organizations conduct proactive security audits of cloud service providers, software providers, hardware manufacturers, professional services vendors that install and customize IT systems, and VARs/distributors that deliver IT equipment and/or services.

|

Cyberのサプライチェーンの保証最良の方法は組織が彼等のすべて使用される保証プロセス、プロシージャおよび技術の安全装置をそれ製造者査定することを定める。 それのcybersecurityの練習を測定するためには売り手は、ある重大な下部組織の組織それをシステム、およびそれを装置やサービス渡すディストリビューターまたはVARs取付け、カスタマイズする雲のサービス・プロバイダの順向のセキュリティ監査を、ソフトウェア販売業者、ハードウェアの製造業者、専門職業的業務の売り手行なう。

|

|

Are these security audits standard practice? ESG research reveals mixed results. On average, just under 50% of critical infrastructure organizations always audit all types of IT suppliers, a marked improvement from 2010 when 28% of critical infrastructure organizations always audited their IT suppliers. Nevertheless, there is still plenty of room for improvement. For example, 18% of organizations do not audit the security processes and procedures of resellers, VARs, and distributors at present. As the Snowden incident indicates, these IT distribution specialists can be used for supply chain interdiction for introducing malicious code, firmware, or backdoors into IT equipment to conduct a targeted attack or industrial espionage (see Figure 8).

|

これらのセキュリティ監査は標準的技法であるか。 ESGの研究はまちまちな結果を明らかにする。 平均して、ちょうど重大な下部組織の組織の50%以下すべてのタイプのそれ製造者、重大な下部組織の組織の28%が彼等のそれを製造者常に監査した2010年からのマーク付きの改善常に監査しなさい。 それにもかかわらず、静かな沢山の改善のための部屋がある。 例えば、組織の18%は転売者、VARsおよびディストリビューターの保証プロセスそしてプロシージャを現在監査しない。 Snowdenの事件は示すと同時に、これらそれに悪意のあるコード、ファームウェア、または目標とされた攻撃か産業スパイを行なうために裏口を導入することのサプライチェーンの禁止に配分の専門家装置使用することができる(図8を見なさい)。

|

|

IT vendor security audits appear to be a shared responsibility with the cybersecurity team playing a supporting role. General IT management has some responsibility for assessing IT vendor security at two-thirds (67%) of organizations, while the cybersecurity team is responsible in just over half (51%) of organizations (see Figure 9).

|

それは売り手のセキュリティ監査支持の役割を担っているcybersecurityのチームとの共用責任のようである。 大将それは管理cybersecurityのチームは組織の責任がある公正な終わる半分(51%)であるが、組織の3分の2でそれを売り手の保証(67%)査定するための責任を有する(図9を見なさい)。

|

|

These results are somewhat curious. After all, why wouldn’t the cybersecurity team be responsible for IT vendor security audits in some capacity? Perhaps some organizations view IT vendor security audits as a formality, part of the procurement team’s responsibility, or address IT vendor security audits with standard “checkbox” paperwork alone. Regardless of the reason, IT vendor security audits will provide marginal value without hands-on cybersecurity oversight throughout the process.

|

これらの結果は幾分好奇心が強い。 結局、cybersecurityのチームはなぜそれを容量の売り手のセキュリティ監査担当しないか。 多分ある組織は正式、調達のチームの責任の一部分としてそれを売り手のセキュリティ監査見るか、または単独で標準的な「チェックボックス」の書類事務の売り手のセキュリティ監査演説する。 理由にもかかわらず、それはプロセス中の実地cybersecurityの手落ちなしで売り手のセキュリティ監査最底限の価値を提供する。

|

|

IT vendor security audits vary widely in terms of breadth and depth, so ESG wanted some insight into the most common mechanisms used as part of the audit process. Just over half (54%) of organizations conduct a hands-on review of their vendors’ security history; 52% review documentation, processes, security metrics, and personnel related to their vendors’ cyber supply chain security processes; and 51% review their vendors’ internal security audits (see Figure 10).

|

それは幅および深さの点では売り手のセキュリティ監査広く変わる、従ってESGは監査プロセスの一部として使用された共通のメカニズムに洞察力がほしいと思った。 組織の公正な終わる半分(54%)は売り手のの実地検討を」保証歴史行なう; 52%の検討ドキュメンテーション、プロセス、保証測定基準および人員は彼らの売り手のに」 cyberのサプライチェーンの保証プロセス関連していた; そして51%の検討売り手の」内部安全保護監査(図10を見なさい)。

|

|

Of course, many organizations include several of these mechanisms as part of their IT vendor security audits to get a more comprehensive perspective. Nevertheless, many of these audit considerations are based upon historical performance. ESG suggests that historical reviews be supplemented with some type of security monitoring and/or cybersecurity intelligence sharing so that organizations can better assess cyber supply chain security risks in real time.

|

当然、多くの組織は彼等のの一部として広範囲の見通しを得るためにこれらのメカニズムの複数をそれ売り手のセキュリティ監査含んでいる。 それにもかかわらず、これらの監査の考察の多数は歴史的性能に基づいている。 ESGは組織がよりよく実質の時間のcyberのサプライチェーンのセキュリティ上の問題を査定できるように歴史的検討がある種の通信保全監査とおよび/または共有するcybersecurityの知性補われることを提案する。

|

|

To assess the cybersecurity policies, processes, and controls with consistency, all IT vendor security audits should adhere to a formal, documented methodology. ESG research indicates that half of all critical infrastructure organizations conduct a formal security audit process in all cases, while the other half have some flexibility to deviate from formal IT vendor security audit processes on occasion (see Figure 11). It is worth noting that 57% of financial services organizations have a formal security audit process for IT vendors that must be followed in all cases, as opposed to 47% of organizations in other industries. This is another indication that financial services firms tend to have more advanced and stringent cybersecurity policies and processes than those from other industries.

|

一貫性のcybersecurity方針、プロセスおよび制御を査定するため、形式的なべきであるすべて、文書化された方法に売り手のセキュリティ監査付着させる。 ESGの研究は残りの半分に形式的から逸脱する柔軟性がそれあるがすべての重大な下部組織の組織の半分が形式的なセキュリティ監査プロセスをいずれの場合も行なうことを示す、時々売り手のセキュリティ監査プロセス(図11を見なさい)。 金融サービスの組織の57%に他の企業で組織の47%に対してそれのための形式的なセキュリティ監査プロセスがいずれの場合も続かれなければならない売り手あることは無益である。 これはあり金融サービスの会社に他の企業からのそれらより進められ、厳しいcybersecurity方針そしてプロセスがちであるもう一つの徴候である。

|

|

IT vendor security audits involve data collection, analysis, evaluations, and final decision-making. From a scoring perspective, just over half (51%) of critical infrastructure organizations employ formal metrics/scorecards where IT vendors must attain a certain cybersecurity profile to qualify as an approved supplier. The remainder of critical infrastructure organizations have less stringent guidelines—32% have a formal vendor review process but no specific metrics for vendor qualification, while 16% conduct an informal review process (see Figure 12).

|

それは売り手のセキュリティ監査data collection、分析、評価および最終的な意志決定を含む。 記録の見通しから、重大な下部組織の組織のちょうど余分の半分(51%)は公認の製造者として修飾するために売り手ある特定のcybersecurityのプロフィールを達成しなければならない形式的な測定基準をかスコアカードを用いる。 重大な下部組織の組織の残りにより少なく厳しい指針32%がが16%の行ない非公式の検討プロセス形式的な売り手の検討プロセス売り手の資格のための特定の測定基準があるのをないが、(図12を見なさい)。

|

|

Overall, ESG research indicates that many critical organizations are not doing enough due diligence with IT vendor cybersecurity audits. To minimize the risk of a cyber supply chain security incident, vendor audit best practices would have to include the following three steps:

|

全体的にみて、ESGの研究は多くの重大な組織がそれの十分な適当な注意を売り手のcybersecurityの監査していないことを示す。 cyberのサプライチェーンの保証事件の危険を最小にするためには、売り手の監査の最良の方法は次の3つのステップを含まなければならない:

|

|

1. Organization always audits the internal security processes of strategic IT vendors.

|

1. 構成は戦略的の内部保全プロセスをそれ売り手常に監査する。

|

|

1. Organization uses a formal standard audit process for all IT vendor audits.

|

1. 構成はすべてのために形式的な標準的な監査プロセスをそれ売り手の監査使用する。

|

|

2. Organization employs formal metrics/scorecards where IT vendors must exceed a scoring threshold to qualify for IT purchasing approval.

|

2. 構成はそれのために修飾するために承認を購入している売り手記録の境界を超過しなければならない形式的な測定基準をかスコアカードを用いる。

|

|

When ESG assessed critical infrastructure organizations through this series of IT vendor audit steps, the results were extremely distressing. For example, on average, only 14% of the total survey population adhered to all three best practice steps when auditing the security of their strategic infrastructure vendors (see Table 3). Since strategic infrastructure vendors are audited most often, it is safe to assume that less than 14% of the total survey population follows these best practices when auditing the security of software vendors, cloud service providers, professional services firms, and distributors.

|

ESGがこの一連のそれによって重大な下部組織の組織を売り手の監査のステップ査定したときに、結果は非常に悲惨だった。 例えば戦略的な下部組織の売り手の保証を監査する場合の、平均すると、すべての3つのよい練習のステップに付着する総調査の人口の14%だけ(表3を見なさい)。 戦略的な下部組織の売り手が最も頻繁に監査されるので、ソフトウェア販売業者、雲のサービス・プロバイダの保証を監査するとき総調査の人口の14%以下これらの最良の方法に続くと仮定することは安全である、専門職業的業務は、ディストリビューター固まり。

|

Table 3. Incidence of Best Practices for IT Vendor Security Audits

|

It is also worth noting that ESG data shows marginal improvements regarding IT vendor security auditing best practices in the last five years. In 2010, only 10% of critical infrastructure organizations followed all six best practice steps, while 14% do so in 2015. Clearly, there is still a lot of room for improvement.

|

ESGデータが最後の5年にそれに関する最底限の改善に最良の方法を監査する売り手の保証を示すことはまた無益である。 2010年に、14%は2015年にそうするが、重大な下部組織の組織の10%だけは6つのよい練習のステップにすべて従った。 明らかに、今でも改善のための多くの部屋がある。

|

|

Regardless of security audit deficiencies, many critical infrastructure organizations are somewhat bullish about their IT vendors’ security. On average, 41% of cybersecurity professionals rate all types of IT vendors as excellent in terms of their commitment to and communications about their internal security processes and procedures, led by strategic infrastructure vendors achieving an excellent rating from 49% of the cybersecurity professionals surveyed (see Figure 13).

|

セキュリティ監査の不足にもかかわらず、多くの重大な下部組織の組織は彼等のについて幾分強気それ売り手の」保証である。 平均して、cybersecurityの専門家の41%は彼らの内部保全のプロセスおよびプロシージャについての彼らの責任にの点では優秀ように調査されるcybersecurityの専門家の49%から優秀な評価を達成している戦略的な下部組織の売り手が導くすべてのタイプのそれ売り手およびコミュニケーション評価する(図13を見なさい)。

|

|

Critical infrastructure organizations gave their IT vendors more positive security ratings in 2015 compared with 2010. For example, only 19% of critical infrastructure organizations rated their strategic infrastructure vendors as excellent in 2010 compared with 49% in 2015. Many IT vendors have recognized the importance of building cybersecurity into products and processes during this timeframe and are much more forthcoming about their cybersecurity improvements. Furthermore, critical infrastructure organizations have increased the amount of vendor security due diligence over the last five years, leading to greater visibility and improved vendor ratings.

|

重大な下部組織の組織は彼等のそれを売り手2010年と比較された2015のより肯定的な保証評価与えた。 例えば、重大な下部組織の組織の19%だけは2015年に49%と比較された2010で優秀ように戦略的な下部組織の売り手を評価した。 多数それはプロダクトに売り手cybersecurityおよびこの時間枠の間にプロセスを造る重要性を確認し、cybersecurityの改善についてはるかに迫っている。 なお、重大な下部組織の組織はより大きい可視性および改善された売り手の評価をもたらす最後の5年にわたる売り手の保証適当な注意の量を高めた。

|

|

The news isn’t all good as at least 12% of critical infrastructure organizations are only willing to give their IT vendors’ internal security processes and procedures a satisfactory, fair, or poor rating. ESG is especially concerned with ratings associated with resellers, VARs, and distributors since 24% of critical infrastructure organizations rate their internal security processes and procedures as satisfactory, fair, or poor. This is especially troubling since Figure 10 reveals that 18% of critical infrastructure organizations do not perform security audits on resellers, VARs, and distributors. Based upon all of this data, it appears that critical infrastructure organizations remain vulnerable to cybersecurity attacks (like supply chain interdiction) emanating from resellers, VARs, and distributors.

|

ニュースは重大な下部組織の組織の少なくとも12%が彼等のそれだけを与えて喜んで売り手」内部保全のプロセスおよびプロシージャ満足のであるので完全によく、市、または悪い評価ではない。 ESGは転売者とVARs、関連付けられる評価に特にかかわって重大な下部組織の組織の24%以来のディストリビューターは、市満足ように内部保全のプロセスおよびプロシージャ、または貧乏人評価する。 これは重大な下部組織の組織の18%は転売者、VARsおよびディストリビューターのセキュリティ監査を行わないことを図10が明らかにするので特に厄介である。 重大な下部組織の組織が転売者、VARsおよびディストリビューターから出るcybersecurityの攻撃に傷つきやすく(サプライチェーンの禁止のように)残るこのデータすべてに基づいて、ようである。

|

|

IT hardware and software is often developed, tested, assembled, or manufactured in multiple countries with varying degrees of patent protection or legal oversight. Some of these countries are known “hot beds” of cybercrime or even state-sponsored cyber-espionage. Given these realities, one would think that critical infrastructure organizations would carefully trace the origins of the IT products purchased and used by their firms.

|

それは頻繁にパテントの保護または法的手落ちの様々なレベルの多数の国でハードウェアおよびソフトウェア開発されるか、テストされるか、組み立てられるか、または製造される。 これらの国のいくつかはcybercrimeまた更に政府が支援するcyber諜報活動の知られていた「熱いベッド」である。 これらの現実を与えられて、1つは重大な下部組織の組織が注意深くの起源をそれ会社によって購入され、使用されたプロダクト辿ると考える。

|

|

ESG’s data suggests that most firms are at least somewhat certain about the geographic lineage of their IT assets (see Figure 14). It should also be noted that there have been measurable improvements in this area as 41% of critical infrastructure organizations are very confident that they know the country in which their IT hardware and software products were originally developed and/or manufactured compared with only 24% in 2010. Once again, ESG attributes this progress to improvements in IT vendor security due diligence, greater supply chain security oversight within the IT vendor community, and increased overall cyber supply chain security awareness across the entire cybersecurity community over the past five years.

|

ESGのデータはほとんどの会社が少なくとも彼等のの地理的な血統について幾分確かそれ資産であることを提案する(図14を見なさい)。 彼等のハードウェアおよびソフトウェア製品最初に2010年に24%だけと比較されて開発されたりおよび/または製造された国を知っていること重大な下部組織の組織の41%が非常に確信しているのでこの区域に測定可能な改善がずっとあることがまた注意されるべきである。 再度、ESGはそれの改善にこの進歩をの内の売り手の保証適当な注意、より大きいサプライチェーンの保証手落ちそれ売り手のコミュニティ、および過去5年にわたる全体のcybersecurityのコミュニティを渡る高められた全面的なcyberのサプライチェーンの保証意識帰因させる。

|

|

While cybersecurity professionals gave positive ratings to their IT vendors’ security and are fairly confident about the origins of their IT hardware and software, they remain vulnerable because of insecure hardware and software that somehow circumvent IT vendor security audits, fall through the cracks, and end up in production environments. In fact, the majority (58%) of critical infrastructure organizations admit that they use insecure products and/or services that are a cause for concern (see Figure 15). One IT product or service vulnerability could represent the proverbial “weak link” that leads to a cyber-attack on the power grid, ATM network, or water supply.

|

cybersecurityの専門家が彼等のに肯定的な評価にそれを売り手」保証与え、彼等のの起源についてかなり確信しているそれハードウェアおよびソフトウェア間、生産環境にどうかしてそれを売り手のセキュリティ監査避け、無視され、そして行きつく不確かなハードウェアおよびソフトウェアのために傷つきやすく残る。 実際はそれらが不安の原因であるサービスや不確かなプロダクトを使用することを、重大な下部組織の組織の大半(58%)は是認する(図15を見なさい)。 1つそれはプロダクトかサービス脆弱性諺の「弱い連結」それが電力網でにcyber攻撃する導く、ATMネットワーク、または給水を表すことができる。

|

Cyber Supply Chain Security and Software Assurance

|

Cyberのサプライチェーンの保証およびソフトウェア保証

|

|

Software assurance is another key tenet of cyber supply chain security as it addresses the risks associated with a cybersecurity attack targeting business software. The U.S. Department of Defense defines software assurance as:

|

ソフトウェア保証はビジネスソフトウェアを目標とするcybersecurityの攻撃と関連付けられる危険に演説するのでcyberのサプライチェーンの保証のもう一つの主主義である。 米国。 国防省はソフトウェア保証を次のように定義する:

|

|

“The level of confidence that software is free from vulnerabilities, either intentionally designed into the software or accidentally inserted at any time during its lifecycle, and that the software functions in the intended manner.”

|

「ソフトウェアが計画的にソフトウェアにである組み込まれているまたは偶然ライフサイクルの間にいつでも挿入される脆弱性から自由、意図されていた方法でソフトウェアによってが」。作用し信任のレベル

|

|

Critical infrastructure organizations tend to have sophisticated IT requirements, so it comes as no surprise that 40% of organizations surveyed develop a significant amount of software for internal use while another 41% of organizations develop a moderate amount of software for internal use (see Figure 16).

|

重大な下部組織の組織は条件それを複雑にしがちである、従って組織のもう41%が内部使用のためのソフトウェアの適当な量を開発する間、調査される組織の40%がかなり内部使用のためのソフトウェアを開発する驚きとして来ない(図16を見なさい)。

|

|

Software vulnerabilities continue to represent a major threat vector for cyber-attacks. For example, the 2015 Verizon Data Breach and Investigations Report found that web application attacks accounted for 9.4% of incident classification patterns within the confirmed data breaches. Since any poorly written, insecure software could represent a significant risk to business operations, ESG asked respondents to rate their organizations on the security of their internally developed software. The results vary greatly: 47% of respondents say that they are very confident in the security of their organization’s internally developed software, but 43% are only somewhat confident and another 8% remain neutral (see Figure 17).

|

ソフトウェア脆弱性はcyber攻撃する主要な脅威のベクトルをのための表し続ける。 例えばWebアプリケーションの攻撃が確認されたデータ違反内の事件の分類パターンの9.4%を占めたことを、2015年のVerizonデータ違反および調査は分られて報告する。 不完全に書かれている以来不確かなソフトウェアは運営業務に重要な危険を表すことができるESGは被告に彼らの内部的に開発されたソフトウェアの保証の彼らの組織を評価するように頼んだ。 結果は非常に変わる: 被告の47%は構成の内部的に開発されたソフトウェアの保証で非常に確信している、43%は幾分確信してただ、がもう8%は中立に残ると言う(図17を見なさい)。

|

|

There is a slight increase in the confidence level over the past five years as 36% of cybersecurity professionals working at critical infrastructure organizations were very confident in the security of their organization’s internally developed software in 2010 compared with 47% today. But this is a marginal improvement at best.

|

重大な下部組織の組織で働いているcybersecurityの専門家の36%として過去5年にわたる信頼水準にわずかな増加があった47%と今日比較される2010の構成の内部的に開発されたソフトウェアの保証で非常に確信していたがある。 しかしこれは精々最底限の改善である。

|

|

To assess software security more objectively, ESG asked respondents whether their organization ever experienced a security incident directly related to the compromise of internally developed software. As it turns out, one-third of critical infrastructure organizations have experienced one or several security incidents that were directly related to the compromise of internally developed software (see Figure 18).

|

ソフトウェア保証をより客観的に査定するためには、ESGは彼らの構成が直接内部的に開発されたソフトウェアの妥協と関連していた保証事件を経験するかどうか被告に尋ねた。 結局、重大な下部組織の組織の3分の1は内部的に開発されたソフトウェアの妥協と直接関連していた1つのまたは複数の保証事件を経験した(図18を見なさい)。

|

|

From an industry perspective, 39% of financial services firms have experienced a security incident directly related to the compromise of internally developed software compared with 30% of organizations from other critical infrastructure industries. This happens in spite of the fact that financial services tend to have advanced cybersecurity skills and adequate cybersecurity resources. ESG finds this data particularly troubling since a cyber-attack on a major U.S. bank could disrupt the domestic financial system, impact global markets, and cause massive consumer panic.

|

企業の見通しから、金融サービスの会社の39%は直接他の重大な下部組織工業からの組織の30%と比較される内部的に開発されたソフトウェアの妥協と関連している保証事件を経験した。 これは金融サービスがcybersecurityの技術および十分なcybersecurity資源を進めがちであるその事実にもかかわらず起こす。 ESGは主要な米国でcyber攻撃しなさいのでこのデータを特に悩むことを見つける。 銀行は国内財政システムを破壊し、全体的な市場に影響を与え、大きい消費者パニックを引き起こすことができる。

|

|

Critical infrastructure organizations recognize the risks associated with insecure software and are actively employing a variety of security controls and software assurance programs. The most popular of these is also the easiest to implement as 51% of the organizations surveyed have deployed application firewalls to block application-layer cyber-attacks such as SQL injections and cross-site scripting (XSS). In addition to deploying application firewalls, about half of the critical infrastructure organizations surveyed also include security testing tools as part of their software development processes, measuring their software security against publicly available standards, providing secure software development training to internal developers, and adopting secure software development lifecycle processes (see Figure 19). Of course, many organizations are engaged in several of these activities simultaneously in order to bolster the security of their homegrown software.

|

重大な下部組織の組織は不確かなソフトウェアと関連付けられる危険を確認し、積極的に色々な機密管理およびソフトウェア保証プログラムを用いている。 適用層を妨げるために調査されるSQLの注入および十字場所の台本を書くことのような組織の51%が適用防火壁をcyber攻撃する配置したのでこれらの普及したのまた最も実行し易い(XSS)。 配置の適用防火壁に加えて、また調査される重大な下部組織の組織の半分についてソフトウェア開発プロセスの一部として保証テストツールを含んで、ソフトウェア保証を一般公開された標準に対して測定し、訓練し、安全なソフトウェア開発のライフサイクルプロセスを採用する安全なソフトウェア開発を内部開発者に提供する(図19を見なさい)。 内地産ソフトウェアの保証を強化するために当然、多くの組織はこれらの活動の複数で同時に従事している。

|

|

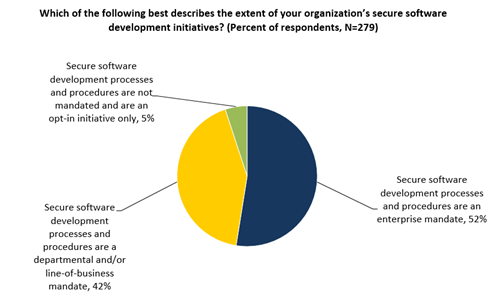

Secure software development programs are certainly a step in the right direction, but software assurance effectiveness is a function of two factors: the types of programs employed and the consistency of these programs. ESG research reveals that just over half of critical infrastructure organizations treat secure software development processes and procedures as an enterprise mandate, so it’s likely that these firms have a consistent secure software development methodology across the organization.

|

安全なソフトウェア開発プログラムは確かに正しい方向のステップであるが、ソフトウェア保証の有効性は2つの要因の機能である: 用いられるプログラムのタイプおよびこれらのプログラムの一貫性。 ESGの研究はこれらの会社に構成を渡る一貫した安全なソフトウェア開発方法論があることは重大な下部組織の組織のちょうど余分の半分が企業の命令として安全なソフトウェア開発のプロセスおよびプロシージャを扱う、従って本当らしいことを明らかにする。

|

|

Alternatively, 42% of the critical infrastructure organizations surveyed implement secure software development processes and procedures as departmental or line-of-business mandates (see Figure 20). Decentralized software security processes like these can lead to tremendous variability where some departments institute strong software assurance programs while others do not. Furthermore, secure software development programs can vary throughout the enterprise where one department provides training and formal processes while another simply deploys an application firewall. As the old saying goes, “One bad apple can spoil the whole bunch”—a single department that deploys insecure internally developed software can open the door to damaging cyber-attacks that impact the entire enterprise and disrupt critical infrastructure services like food distribution, health care, or telecommunications.

|

また、調査される部門かラインのビジネス命令として重大な下部組織の組織の42%は安全なソフトウェア開発のプロセスおよびプロシージャを実行する(図20を見なさい)。 これらのような分散させていたソフトウェア保証プロセスはある部門が強いソフトウェア保証プログラムを設ける途方もない可変性を他はがもたらす場合がある。 なお、安全なソフトウェア開発プログラムは1つの部門が訓練および形式的なプロセスを提供する企業中別のものが適用防火壁を単に配置する間、変わることができる。 古い格言が行くと同時に、「1個の悪いりんご全束」をだめにすることができる-損傷に不確かな内部的に開発されたソフトウェアをドアを開けることができるcyber攻撃すること影響全体の企業配置する食品流通、ヘルスケア、またはテレコミュニケーションのような重大な下部組織サービスを破壊し、単一の部門は。

|

|

Critical infrastructure organizations are implementing secure software development programs for a number of reasons, including adhering to general cybersecurity best practices (63%), meeting regulatory compliance mandates (55%), and even lowering costs by fixing software security bugs in the development process (see Figure 21).

|

重大な下部組織の組織は一般的なcybersecurityの最良の方法(63%)に付着を含むいくつかの理由のための安全なソフトウェア開発プログラムを、実行し、規定する承諾の命令(55%)、および均一な低下費用に開発プロセスのソフトウェア保証虫の修理によって会う(図21を見なさい)。

|

|

It is also worth noting that 27% of critical infrastructure organizations are establishing secure software development programs in anticipation of new legislation. These organizations may be thinking in terms of the NIST cybersecurity framework (CSF) first introduced in February 2014. Although compliance with the CSF is voluntary today, it may evolve into a common risk management and regulatory compliance standard that supersedes other government and industry regulations like FISMA, GLBA, HIPAA, and PCI-DSS in the future. Furthermore, the CSF may also become a standard for benchmarking IT risk as part of cyber insurance underwriting and may be used to determine organizations’ insurance premiums. Given these possibilities, critical infrastructure organizations would be wise to consult the CSF, assess CSF recommendations for software security, and use the CSF to guide their software security processes and controls wherever possible.

|

重大な下部組織の組織の27%が新しい立法を予想して安全なソフトウェア開発プログラムを確立していることはまた無益である。 これらの組織は最初に2014年2月にもたらされるNISTのcybersecurityフレームワーク(CSF)の点では考えるかもしれない。 CSFの承諾は自発的な今日であるが、FISMA、GLBA、HIPAAおよびPCI-DSSのような他の政府および企業の規則に将来取って代わる共通のリスク管理および規定する承諾の標準に展開するかもしれない。 なお、CSFはまた署名するcyberの保険の一部としてそれを記録するための標準に危険なり、保険料組織の」定めるのに使用されるかもしれない。 これらの可能性を与えられて、重大な下部組織の組織はCSFに相談し、ソフトウェア保証のためのCSFの推薦を査定し、CSFをソフトウェア保証プロセスおよび制御を可能な限り導くのに使用して賢い。

|

|

Aside from the ongoing software security actions taken today, critical infrastructure organizations also have future plans—28% plan to include specific security testing tools as part of software development, 25% will add web application firewalls to their infrastructure, and 24% will hire developers and development managers with secure software development skills (see Figure 22). These ambitious plans indicate that CISOs recognize their software development security deficiencies and are taking precautions in order to mitigate risk.

|

今日とられる進行中のソフトウェア保証処置は別として重大な下部組織の組織にまたソフトウェア開発の一部として特定の保証テストツールを含む未来の計画28%の計画がある25%は下部組織にWebアプリケーションの防火壁を加え、24%は安全なソフトウェア開発の技術の開発者そして開発のマネージャーを雇う(図22を見なさい)。 これらの意欲的な計画はCISOsがソフトウェア開発の保証不足を確認し、危険を軽減するために注意を取っていることを示す。

|

|

Some software development, maintenance, and testing activities are often outsourced to third-party contractors and service providers. This is the case at half of the critical infrastructure organizations that participated in this ESG research survey (see Figure 23).

|

あるソフトウェア開発、維持およびテストの活動は頻繁に第三者の建築業者およびサービス・プロバイダに外部委託される。 これはこのESGの研究の調査に加わった重大な下部組織の組織の半分に事実である(図23を見なさい)。

|

|

As part of these relationships, many critical infrastructure organizations place specific cybersecurity contractual requirements on third-party software development partners. For example, 43% mandate security testing as part of the acceptance process, 41% demand background checks on third-party software developers, and 41% review software development projects for security vulnerabilities (see Figure 24).

|

これらの関係の一部として、多くの重大な下部組織の組織は第三者のソフトウェア開発パートナーに特定のcybersecurityの契約上の条件を置く。 例えば、第三者ソフトウェア開発者の受諾プロセス、41%の要求の素性調査、およびセキュリティーの脆弱性のために41%の検討のソフトウェア開発のプロジェクトの一部としてテストする43%の命令保証(図24を見なさい)。

|

Cybersecurity, Critical Infrastructure Security Professionals, and the U.S. Federal Government

|

Cybersecurity、重大な下部組織の保証専門家および米国。 連邦政府

|

|

ESG research indicates a pattern of persistent cybersecurity incidents at U.S. critical infrastructure organizations over the past few years. Furthermore, security professionals working in critical infrastructure industries believe that the cyber-threat landscape is more dangerous today than it was two years ago.

|

ESGの研究は米国で耐久性があるcybersecurityの事件のパターンを示す。 過去数年間にわたる重大な下部組織の組織。 なお、重大な下部組織工業でcyber脅威の景色がより危ない今日であることをよりそれだった2年信じる働いている保証専門家は前に。

|

|

To address these issues, President Obama and various other elected officials proposed several cybersecurity programs such as the NIST cybersecurity framework and an increase in threat intelligence sharing between critical infrastructure organizations and federal intelligence and law enforcement agencies. Of course, federal cybersecurity discussions are nothing new. Recognizing a national security vulnerability, President Clinton first addressed critical infrastructure protection (CIP) with Presidential Decision Directive 63 (PDD-63) in 1998. Soon thereafter, Deputy Defense Secretary John Hamre cautioned the U.S. Congress about CIP by warning of a potential “cyber Pearl Harbor.” Hamre stated that a devastating cyber-attack, “… is not going to be against Navy ships sitting in a Navy shipyard. It is going to be against commercial infrastructure.”

|

これらの問題を扱うためには、Obama大統領および他の色々な選ばれた役員は重大な下部組織の組織および中央政府知性および執行機関の間で共有する脅威の知性のNISTのcybersecurityフレームワークそして増加のような複数のcybersecurityプログラムを提案した。 当然、中央政府cybersecurityの議論は何も新しいことではない。 国家安全保障の脆弱性を確認して、クリントン大統領最初に1998年に大統領決定の指令63 (PDD-63)を用いる重大な下部組織の保護(CIP)に演説した。 その後すぐ、ジョンHamre代理国防長官は米国に警告した。 潜在的な「cyber真珠湾の警告によるCIPについての議会」。の Hamreは破壊的のcyber攻撃することを、「…海軍造船所に坐る海軍船に対してあることを行っていない示した。 それは商業下部組織に対してあることを行っている」。

|

|

Security professionals working at critical infrastructure industries have been directly or indirectly engaged with U.S. Federal Government cybersecurity programs and initiatives through several Presidential administrations. Given this lengthy timeframe, ESG wondered whether these security professionals truly understood the U.S. government’s cybersecurity strategy. As seen in Figure 31, the results are mixed at best. One could easily conclude that the data resembles a normal curve where the majority of respondents believe that the U.S. government’s cybersecurity strategy is somewhat clear while the rest of the survey population is distributed between those who believe that the U.S. government’s cybersecurity strategy is very clear and those who say it is unclear.

|

重大な下部組織工業で働いている保証専門家は米国と直接的または間接的に従事していた。 複数の大統領管理を通した連邦政府のcybersecurityのプログラムそして率先。 この長い時間枠を与えられて、ESGはこれらの保証専門家が偽りなく米国を理解したかどうか疑問に思った。 政府のcybersecurityの作戦。 図31に見られるように、結果は精々混合される。 1つは容易にデータが被告の大半がことを米国信じる正常なカーブに類似していることを結論できる。 政府のcybersecurityの作戦は調査の人口の残りがことを米国信じる人の間で配られる間、幾分明確である。 政府のcybersecurityの作戦は非常に明確であり、それを言う人は明白でない。

|

|

ESG views the results somewhat differently. In spite of over 20 years of U.S. federal cybersecurity discussions, many security professionals remain unclear about what the government plans to do in this space. Clearly, the U.S. Federal Government needs to clarify its mission, its objectives, and its timeline with cybersecurity professionals to gain their trust and enlist their support for public/private programs.

|

ESGは結果を幾分別様に見る。 に20年間の米国にもかかわらず。 中央政府cybersecurityの議論は、多くの保証専門家このスペースでするべき政府の計画何について明白でなく残る。 明らかに、米国の連邦政府はcybersecurityの専門家との代表団、目的および彼らの信頼を得、公共か私用プログラムのための彼らのサポートを入隊するためにタイムラインを明白にする必要がある。

|

|

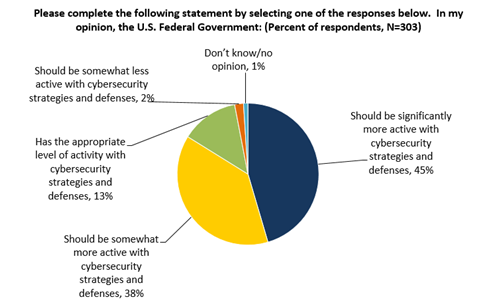

While critical infrastructure security professionals may be uncertain about the U.S. Federal Government’s strategy, they would also like to see Washington become more engaged. Nearly half (45%) of critical infrastructure organizations believe that the U.S. Federal Government should be significantly more active with cybersecurity strategies and defenses while 38% believe that the U.S. Federal Government should be somewhat more active with cybersecurity strategies and defenses (see Figure 32).

|

重大間下部組織の保証専門家は米国について不確かかもしれない。 連邦政府の作戦、彼らはまたワシントン州がより従事させていてなるのを見ることを望む。 重大な下部組織の組織のほぼ半分(45%)はことを米国信じる。 連邦政府は38%がことを米国信じる間、cybersecurityの作戦および防衛と活発なべきである。 連邦政府はcybersecurityの作戦および防衛と幾分活発なべきである(図32を見なさい)。

|

|

Finally, ESG asked the entire survey population of security professionals what types of cybersecurity actions the U.S. Federal Government should take. Nearly half (47%) believe that Washington should create better ways to share security information with the private sector. This aligns well with President Obama’s executive order urging companies to share cybersecurity threat information with the U.S. Federal Government and one another. Cybersecurity professionals have numerous other suggestions as well. Some of these could be considered government cybersecurity enticements. For example, 37% suggest more funding for cybersecurity education programs while 36% would like more incentives like tax breaks or matching funds for organizations that invest in cybersecurity. Alternatively, many cybersecurity professionals recommend more punitive or legislative measures—44% believe that the U.S. Federal Government should create a “black list” of vendors with poor product security (i.e., the cybersecurity equivalent of a scarlet letter), 40% say that the U.S. Federal Government should limit its IT purchasing to vendors that display a superior level of security, and 40% endorse more stringent regulations like PCI DSS or enacting laws with higher fines for data breaches (see Figure 33).

|

最後に、ESGはどのようなcybersecurityの行為米国か保証専門家の全体の調査の人口に尋ねた。 連邦政府は取るべきである。 ワシントン州が民間部門とセキュリティ情報を共有するよりよい方法を作成するべきであることをほぼ半分(47%)信じなさい。 これは米国とcybersecurityの脅威情報を共有するように会社をせき立てる大統領の政令とObama'sよく一直線に並ぶ。 連邦政府および互い。 Cybersecurityの専門家に多数他の提案がまたある。 これらのいくつかは政府のcybersecurityの誘惑として考慮することができる。 例えば、37%は36%がcybersecurityに投資する組織のための税額控除または見合い調達のようなより多くの刺激を好む間、cybersecurityの教育プログラムのためのより多くの資金を提案する。 また、多くのcybersecurityの専門家は刑罰を推薦するまたは立法測定44%はことを米国信じる。 連邦政府は悪いプロダクト保証(深紅手紙のすなわち、cybersecurityの等量)と40%言うと米国売り手の「黒いリスト」を作成するべきである。 連邦政府は優秀なセキュリティレベルを、40%はPCI DSSのようなより厳しい規則に裏書きする表示するまたはデータのためのより高い罰金との法律を制定することは破る売り手に購入するそれを限るべきで(図33を見なさい)。

|

|

Of course, it’s unrealistic to expect draconian cybersecurity policies and regulations from Washington, but the ESG data presents a clear picture: Cybersecurity professionals would like to see the U.S. Federal Government use its visibility, influence, and purchasing power to produce cybersecurity “carrots” and “sticks.” In other words, Washington should be willing to reward IT vendors and critical infrastructure organizations that meet strong cybersecurity metrics and punish those that cannot adhere to this type of standard.

|

当然、ワシントン州からの過酷なcybersecurityの方針そして規則を期待することは非現実的であるがESGデータは明確な映像を示す: Cybersecurityの専門家は米国の連邦政府の使用を見ることを望む可視性、影響および購買力cybersecurity 「にんじん」および「棒作り出す」。を すなわち、それに報酬を与えて強いcybersecurityの測定基準にワシントン州は喜んで会うべきで、このタイプの標準に付着できないワシントン州を罰する重大な下部組織の組織および売り手。

|

|

|