|

|

Research Findings

The Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity Landscape

|

重要基础设施Cybersecurity风景

|

Today’s Outlook on Cybersecurity Threats More Bleak than in 2013

|

2013年今天外型在Cybersecurity威胁荒凉比

|

|

Defending against cyber-attacks represents a perpetual battle for critical infrastructure organizations facing an increasingly dangerous threat landscape. In fact, 31% of security professionals working at critical infrastructure organizations believe that the threat landscape today is much worse than it was two years ago, while another 36% say it is somewhat worse (see Figure 1).

|

保卫反对cyber攻击代表一次永久争斗为面对一个越来越危险威胁风景的重要基础设施组织。 实际上, 31%工作在重要基础设施组织的安全专家相信威胁风景今天比它二年前坏,而另外36%言它是有些更坏的(参见图1)。

|

|

It is interesting to note that ESG asked this same question in its 2010 research project,1 and it produced strikingly similar results—68% of respondents said that the threat landscape was worse in 2010 compared with 2008. Clearly, the threat landscape is getting more hazardous on an annual basis with no letup in sight. ESG finds this data particularly troubling. U.S. citizens depend upon critical infrastructure organizations for the basic necessities of modern society like food, water, fuel, and telecommunications services. Given the increasingly dangerous threat landscape, critical infrastructure organizations are tasked with maintaining important everyday services and defending their networks from a growing army of cyber-criminals, hacktivists, and nation state actors.

|

注意到, ESG在它的2010研究计划问这同样问题是有趣的, 1 并且它导致了应答者的相似的结果68%醒目说威胁风景是坏在2010比较2008年。 清楚地,威胁风景在视线内每年得到危害没有停止。 ESG发现这数据特别令人焦虑。 美国. 公民取决于重要基础设施组织为现代社会基本的必要象食物、水、燃料和电信服务。 假使越来越危险威胁风景,重要基础设施组织分配与维护重要每天服务和保卫他们的网络从cyber罪犯、hacktivists和"台独"演员一支增长的军队。

|

|

Note1: Source: ESG Research Report, Assessing Cyber Supply Chain Security Vulnerabilities Within the U.S. Critical Infrastructure, November 2010.

|

Note1 : 来源: ESG研究报告,在美国范围内估计Cyber供应链安全漏洞。 重要基础设施, 2010年11月。

|

|

These beliefs about the increasingly dangerous threat landscape go beyond opinions alone as many critical infrastructure organizations face constant cyber-attacks. A majority (68%) of critical infrastructure organizations experienced a security incident over the past two years, with nearly one-third (31%) experiencing a system compromise as a result of a generic attack (i.e., virus, Trojan, etc.) brought in by a user’s system, 26% reporting a data breach due to lost/stolen equipment, and 25% of critical infrastructure organizations suffering some type of insider attack (see Figure 2). Alarmingly, more than half (53%) of critical infrastructure organizations have dealt with at least two of these security incidents since 2013.

|

这些信仰关于越来越危险威胁风景超出单独观点范围面孔恒定cyber攻击的许多重要基础设施组织。 大多数(68%)重要基础设施组织体验了安全事件在过去二年,当几乎三分之一(31%)体验系统妥协的由于用户的系统(即,病毒、特洛伊人等等)带来的一次普通攻击,遭受知情人攻击的一些个类型26%报告数据突破口由于失去或被窃取的设备和25%重要基础设施组织(参见图2)。 令人挂虑地,更多比一半(53%)重要基础设施组织涉及了至少二这些安全事件自2013年以来。

|

|

Security incidents always come with ramifications associated with time and money. For example, nearly half (47%) of cybersecurity professionals working at critical infrastructure organizations claim that security incidents required significant IT time/personnel for remediation. While this places an unexpected burden on IT and cybersecurity groups, other consequences related to security incidents were far more ominous—36% say that security incidents led to the disruption of a critical business process or business operations, 36% claim that security incidents resulted in the disruption of business applications or IT systems availability, and 32% report that security incidents led to a breach of confidential data (see Figure 3).

|

安全事件总来以分枝与时间和金钱相关。 例如,近一半(47%)工作在重要基础设施组织的cybersecurity专家声称安全事件要求重大它时刻或人员为治疗。 当这在它和cybersecurity小组时安置意想不到的负担,其他后果与安全事件有关是安全事件带领一个重要业务流程或经营活动的中断的更加不祥36%的言, 36%要求安全事件导致中断商业应用或它系统可能利用率和安全事件带领机要数据突破口的32%报告(参见图3)。

|

|

This data should be cause for concern since a successful cyber-attack on critical infrastructure organizations’ applications and processes could result in the disruption of electrical power, health care services, or the distribution of food. Thus, these issues could have a devastating impact on U.S. citizens and national security.

|

这数据应该是令人担心的事,因为成功在重要基础设施组织cyber攻击’应用,并且过程可能导致电能的中断,医疗保健服务或者食物的发行。 因此,这些问题能有对美国的一个破坏性碰撞。 公民和国家安全。

|

Cybersecurity at Critical Infrastructure Organizations

|

Cybersecurity在重要基础设施组织

|

|

Do critical infrastructure organizations believe they have the right cybersecurity policies, processes, skills, and technologies to address the increasingly dangerous threat landscape? The results of that inquiry are mixed at best. On the positive side, 37% rate their organizations’ cybersecurity policies, processes, and technologies as excellent and capable of addressing almost all of today’s threats. It is worth noting that the overall ratings have improved since 2010 (see Table 1). While this improvement is noteworthy, 10% of critical infrastructure security professionals still rate their organization as fair or poor.

|

重要基础设施组织是否相信他们有正确的cybersecurity政策、过程、技能和技术演讲越来越危险威胁风景? 那询问的结果被混合得最好。 在正面边、37%率他们的组织’ cybersecurity政策,过程和技术如优秀和能演讲几乎所有今天威胁。 它值得注意到,总评改善了自2010年以来(参见表1)。 当这改善是显著的时, 10%重要基础设施安全专家仍然对他们的组织如公平或贫寒估计。

|

|

Being able to deal with most threats may be an improvement from 2010, but it is still not enough. This is especially true given the fact that the threat landscape has grown more difficult at the same time. Critical infrastructure organizations are making progress, but defensive measures are not progressing at the same pace as the offensive capabilities of today’s cyber-adversaries and this risk gap leaves all U.S. citizens vulnerable.

|

能应付多数威胁也许是改善从2010年,但它仍然不是足够。 是特别是真实的指定的这事实威胁风景同时增长更加困难。 重要基础设施组织获得进展,但防御措施不进步在节奏和一样今天cyber敌人和这个风险空白的进攻能力离开所有美国。 公民脆弱。

|

Table 1. Respondents Rate Organization’s Cybersecurity Policies

|

Given the national security implications of critical infrastructure, it is not surprising that cybersecurity risk has become an increasingly important board room issue over the past five years. Nearly half (45%) of cybersecurity professionals today rate their organization’s executive management team as excellent, while only 25% rated them as highly in 2010 (see Table 2). Alternatively, 10% rate the executive management team’s cybersecurity commitment as fair or poor in 2015, where 23% rated them so in 2010. These results are somewhat expected given the visible and damaging data breaches of the past few years. Critical infrastructure cybersecurity is also top of mind in Washington with legislators, civilian agencies, and the executive branch. For example, the 2014 National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) cybersecurity framework (CSF) was driven by an executive order and is intended to help critical infrastructure organizations measure and manage cyber-risk more effectively. As a result of all of this cybersecurity activity, corporate boards are much more engaged in cybersecurity than they were in the past, but whether they are doing enough or investing in the right areas is still questionable.

|

假使重要基础设施的国家安全涵义,它不惊奇cybersecurity风险成为了一个越来越重要证券交易经纪人行情室问题在过去五年。 近一半(45%) cybersecurity专家今天对他们的组织的行政管理组估计如优秀, 2010年,而仅25%对他们估计作为高度(参见表2)。 二者择一地, 2015年10%率行政管理组的cybersecurity承诺如公平或贫寒, 2010年的地方23%如此对他们估计。 这些结果有些期望被给过去几年可看见和残损的数据突破口。 重要基础设施cybersecurity也是顶面头脑在华盛顿与立法者、平民代办处和行政分支。 例如,一个行政命令驾驶2014年国家标准技术局(NIST) cybersecurity框架(CSF)和意欲帮助重要基础设施组织措施和更加有效地处理cyber风险。 由于所有这cybersecurity活动, cybersecurity比他们是从前是much more参与公司板,但他们是否做着足够或投资在正确的区域是可疑的。

|

Table 2. Respondents Rate Organization’s Executive Management Team with Regard to Cybersecurity Initiatives

|

Critical infrastructure organizations are modifying their cybersecurity strategies for a number of reasons. For example, 37% say that their organization’s infosec strategy is driven by the need to support new IT initiatives with strong security best practices. This likely refers to IT projects for process automation that include Internet of Things (IoT) technologies. IoT projects can bolster productivity, but they also introduce new vulnerabilities and thus the need for additional security controls. Furthermore, 37% point to protecting sensitive customer data confidentiality and integrity, and 36% call out the need to protect internal data confidentiality and integrity (see Figure 4). These are certainly worthwhile goals, but ESG was surprised that only 22% of critical infrastructures say that their information security strategy is being driven by preventing/detecting targeted attacks and sophisticated malware threats. After all, 67% of security professionals believe that the threat landscape is more dangerous today than it was two years ago, and 68% of organizations have suffered at least one security incident over the past two years. Since critical infrastructure organizations are under constant attack, ESG feels strongly that CISOs in these organizations should be assessing whether they are doing enough to prevent, detect, and respond to modern cyber-attacks.

|

重要基础设施组织修改他们的cybersecurity战略为一定数量的原因。 例如, 37%言他们的组织的需要驾驶infosec战略支持新它主动性以强有力的安全保障最佳的实践。 这可能提到它为包括事的流程自动化射出(IoT)技术互联网。 IoT项目可能支持生产力,但他们也介绍新的弱点和因而对另外的安全控制的需要。 此外, 37%点到保护敏感顾客数据机密和正直和36%召集需要保护内部数据机密和正直(参见图4)。 这些一定是值得的目标,但ESG惊奇仅22%重要基础设施认为防止或查出被瞄准的攻击和复杂malware威胁驾驶他们的信息安全战略。 终究67%安全专家相信威胁风景比它二年前是更加危险的今天,并且68%组织遭受了至少一个安全事件在过去二年。 因为重要基础设施组织受到恒定的攻击, ESG强烈意识到CISOs在这些组织应该估计他们是否做着足够防止,查出,并且反应现代cyber攻击。

|

Cyber Supply Chain Security

|

Cyber供应链安全

|

|

Like many other areas of cybersecurity, cyber supply chain security is growing increasingly cumbersome. In fact, 60% of security professionals say that cyber supply chain security has become either much more difficult (17%) or somewhat more difficult (43%) over the last two years (see Figure 5).

|

象cybersecurity许多其他区域, cyber供应链安全增长越来越笨重。 实际上, 60%安全专家认为cyber供应链安全变得更多困难(17%)或稍微困难(43%)在过去二年期间(参见图5)。

|

|

Why has cyber supply chain security become more difficult? Forty-four percent claim that their organizations have implemented new types of IT initiatives (i.e., cloud computing, mobile applications, IoT, big data analytics projects, etc.), which have increased the cyber supply chain attack surface; 39% say that their organization has more IT suppliers than it did two years ago; and 36% state that their organization has consolidated IT and operational technology security, which has increased infosec complexity (see Figure 6).

|

为什么cyber供应链安全变得更加困难? 百分之四十四个要求他们的组织实施了新型的它主动性(即,云彩计算,流动应用、IoT、大数据analytics项目等等),增加了cyber供应链攻击表面; 39%言他们的组织比它有更多它供应商做了二年前; 并且36%阐明,他们的组织巩固了它和操作的技术安全,增加了infosec复杂(参见图6)。

|

|

This data is indicative of the state of IT today. The fact is that IT applications, infrastructure, and products are evolving at an increasing pace, driving dynamic changes on a constant basis and increasing the overall cyber supply chain attack surface. Over-burdened CISOs and infosec staff find it difficult to keep up with dynamic cyber supply chain security changes, leading to escalating risks.

|

这数据今天是表示的状态它。 事实是它应用、基础设施和产品演变在增长的节奏,驾驶动态变动根据一个恒定的依据并且增加整体cyber供应链攻击表面。 装载过多的CISOs和infosec职员发现它难跟上动态cyber供应链安全变动,导致升级的风险。

|

Cyber Supply Chain Security and Information Technology

|

Cyber供应链安全和信息技术

|

|

Cybersecurity protection begins with a highly secure IT infrastructure. Networking equipment, servers, endpoints, and IoT devices should be “hardened” before they are deployed on production networks. Access to all IT systems must adhere to the principle of “least privilege” and be safeguarded with role-based access controls that are audited on a continuous or regular basis. IT administration must be segmented through “separation of duties.” Networks must be scanned regularly and software patches applied rapidly. All security controls must be monitored constantly.

|

Cybersecurity保护从一高度安全开始它基础设施。 在他们在生产网络之前,部署应该“硬化网络设备、服务器、终点和IoT设备”。 必须遵守“最少特权的”原则和保障它系统以基于角色的存取控制被验核根据一个连续或规则依据对所有的通入。 必须通过“责任的分离分割它管理”。 必须通常扫描网络和迅速地被应用的软件补丁。 必须经常监测所有安全控制。

|

|

These principles are often applied to internal applications, networks, and systems but may not be as stringent with regard to the extensive network of IT suppliers, service providers, business partners, contractors, and customers that make up the cyber supply chain. As a review, the cyber supply chain is defined as:

|

这些原则经常被申请于内部应用、网络和系统,但可能不是如严密关于广泛的网络它供应商、服务提供者、商务伙伴、组成cyber供应链的承包商和顾客。 作为回顾, cyber供应链被定义如下:

|

|

The entire set of key actors involved with/using cyber infrastructure: system end-users, policy makers, acquisition specialists, system integrators, network providers, and software/hardware suppliers. The organizational and process-level interactions between these constituencies are used to plan, build, manage, maintain, and defend the cyber infrastructure.”

|

介入与或使用cyber基础设施的整个套关键演员: 系统终端用户、政策制订者、承购专家、系统集成商、网络提供者和软件或硬件供应商。 这些顾客之间的组织和过程级互作用用于计划,建立,处理,维护和保卫cyber基础设施”。

|

|

To explore the many facets of cyber supply chain security, this report examines:

|

要探索cyber供应链安全许多小平面,这个报告审查:

|

|

The relationships between critical infrastructure organizations and their IT vendors (i.e., hardware, software, and services suppliers as well as system integrators, channel partners, and distributors).

|

重要基础设施组织之间的关系和他们它供营商(即,硬件、软件和服务供应商并且系统集成商、渠道伙伴和经销商)。

|

|

The security processes and oversight applied to critical infrastructure organizations’ software that is produced by internal developers and third parties.

|

安全过程和失察适用了于是由内部开发商和第三方导致的重要基础设施组织’软件。

|

|

Cybersecurity processes and controls in instances where critical infrastructure organizations are either providing third parties (i.e., suppliers, customers, and business partners) with access to IT applications and services, or are consuming IT applications and services provided by third parties (note: throughout this report, this is often referred to as “external IT”).

|

Cybersecurity过程和控制在事例,重要基础设施组织是任一提供的第三方(即,供应商、顾客和商务伙伴)以对它的通入应用和服务或者消耗它第三方和服务提供的应用(笔记: 在这个报告中,这经常指“外部它”)。

|

Cyber Supply Chain Security and IT Suppliers

|

Cyber供应链安全和它供应商

|

|

Cybersecurity product vendors, service providers, and resellers are an essential part of the overall cyber supply chain. Accordingly, their cybersecurity policies and processes can have a profound downstream impact on their customers, their customers’ customers, and so on. Given this situation, critical infrastructure organizations often include cybersecurity considerations when making IT procurement decisions.

|

Cybersecurity产品供营商、服务提供者和转售者是整体cyber供应链的一个主要部分。 相应地,他们的cybersecurity政策和过程可能有对他们的顾客,他们的顾客’顾客的深刻顺流冲击,等等。 在这个情形下,当做出它获得决定时,重要基础设施组织经常包括cybersecurity考虑。

|

|

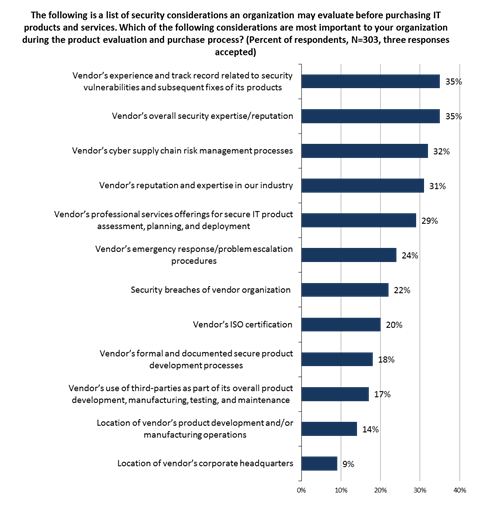

Just what types of cybersecurity considerations are most important? More than one-third (35%) of organizations consider their vendors’ experience and track record related to security vulnerabilities and subsequent fixes. In other words, critical infrastructure organizations are judging vendors by the quality of their software and their responsiveness in fixing software vulnerabilities when they do arise. Another 35% consider their vendors’ overall security expertise and reputation. Close behind, 32% consider their vendors’ cyber supply chain risk management processes, while 31% contemplate their vendors’ reputation and industry expertise (see Figure 7).

|

什么样的cybersecurity考虑是多数重要? 超过三分之一(35%)组织考虑他们的供营商’经验和记录与安全漏洞和随后固定有关。 换句话说,当他们出现时,重要基础设施组织根据他们的软件和他们的快速响应的质量在定象软件弱点判断供营商。 另外35%认为他们的供营商’整体安全专门技术和名誉。 关闭得后边, 32%认为他们的供营商’ cyber供应链风险管理过程,而31%冥想他们的供营商’名誉和产业专门技术(参见图7)。

|

|

Clearly, critical infrastructure organizations have a number of cybersecurity considerations regarding their IT vendors, but many of these concerns, such as vendor reputation and expertise, remain subjective. To counterbalance these soft considerations, CISOs should really establish a list of objective metrics such as the number of CVEs associated with specific ISV applications and the average timeframe between vulnerability disclosure and security patch releases. These types of metrics can be helpful when comparing one IT vendor’s security proficiency against another’s.

|

清楚地,重要基础设施组织有一定数量的cybersecurity考虑关于他们它供营商,但许多这些关心,例如供营商名誉和专门技术,保持主观。 要抵消这些软的考虑, CISOs应该真正地建立客观度规名单例如CVEs的数字与具体ISV应用和平均期限相关在弱点透露和安全补丁发行之间。 当比较一它供营商的安全熟练反对别人时,度规的这些类型可以是有用的。

|

|

Cyber supply chain security best practices dictate that organizations assess the security processes, procedures, and technology safeguards used by all of their IT suppliers. In order to measure the cybersecurity practices of IT vendors, some critical infrastructure organizations conduct proactive security audits of cloud service providers, software providers, hardware manufacturers, professional services vendors that install and customize IT systems, and VARs/distributors that deliver IT equipment and/or services.

|

Cyber供应链安全最佳的实践口授组织估计所有使用的安全过程、规程和技术保障他们它供应商。 为了测量cybersecurity实践它供营商,一些重要基础设施组织举办云彩安装并且定做它系统的服务提供者前摄安全审计、软件提供者、硬件制造商、专业服务交付它设备和服务的供营商和VARs或者经销商。

|

|

Are these security audits standard practice? ESG research reveals mixed results. On average, just under 50% of critical infrastructure organizations always audit all types of IT suppliers, a marked improvement from 2010 when 28% of critical infrastructure organizations always audited their IT suppliers. Nevertheless, there is still plenty of room for improvement. For example, 18% of organizations do not audit the security processes and procedures of resellers, VARs, and distributors at present. As the Snowden incident indicates, these IT distribution specialists can be used for supply chain interdiction for introducing malicious code, firmware, or backdoors into IT equipment to conduct a targeted attack or industrial espionage (see Figure 8).

|

这些安全审计是否是标准操作? ESG研究显露混合结果。 平均,当28%重要基础设施组织总验核了他们它供应商时,在50%重要基础设施组织以下总验核所有类型的它供应商,明显改善从2010年。 然而,有寂静的大量室为改善。 例如, 18%组织当前不验核转售者、VARs和经销商安全过程和规程。 当Snowden事件表明,这些它发行专家可以为供应链禁止使用为介绍恶意代码、固件或者backdoors入它设备举办一种被瞄准的攻击或产业间谍活动(参见图8)。

|

|

IT vendor security audits appear to be a shared responsibility with the cybersecurity team playing a supporting role. General IT management has some responsibility for assessing IT vendor security at two-thirds (67%) of organizations, while the cybersecurity team is responsible in just over half (51%) of organizations (see Figure 9).

|

供营商安全审计看来是一个被共同负担的责任与扮演一个支持的角色的cybersecurity队。 将军它管理有对估计它的一些责任供营商安全在三分之二(67%)组织,而cybersecurity队是负责任的刚好超过半数(51%)组织(参见图9)。

|

|

These results are somewhat curious. After all, why wouldn’t the cybersecurity team be responsible for IT vendor security audits in some capacity? Perhaps some organizations view IT vendor security audits as a formality, part of the procurement team’s responsibility, or address IT vendor security audits with standard “checkbox” paperwork alone. Regardless of the reason, IT vendor security audits will provide marginal value without hands-on cybersecurity oversight throughout the process.

|

这些结果是有些好奇的。 终究为什么cybersecurity队是否不会负责它供营商安全审计在一些容量? 或许有些组织观看它供营商安全审计作为形式,分开获得队的责任或者演讲它供营商安全审计以单独标准“复选框”文书工作。 不管原因,它供营商安全审计将提供临界值,不用实践cybersecurity失察在过程中。

|

|

IT vendor security audits vary widely in terms of breadth and depth, so ESG wanted some insight into the most common mechanisms used as part of the audit process. Just over half (54%) of organizations conduct a hands-on review of their vendors’ security history; 52% review documentation, processes, security metrics, and personnel related to their vendors’ cyber supply chain security processes; and 51% review their vendors’ internal security audits (see Figure 10).

|

它供营商安全审计广泛变化根据广度和深度,因此ESG想要一些洞察入最共同的机制使用作为审计过程一部分。 刚好超过半数(54%)组织举办他们的供营商实践回顾’安全历史; 52%回顾文献、过程、安全度规和人员与他们的供营商关连’ cyber供应链安全过程; 并且51%回顾他们的供营商’内部安全审计(参见图10)。

|

|

Of course, many organizations include several of these mechanisms as part of their IT vendor security audits to get a more comprehensive perspective. Nevertheless, many of these audit considerations are based upon historical performance. ESG suggests that historical reviews be supplemented with some type of security monitoring and/or cybersecurity intelligence sharing so that organizations can better assess cyber supply chain security risks in real time.

|

当然,许多组织包括几个这些之中机制作为他们一部分它供营商安全审计得到更加全面的透视。 然而,许多这些审计考虑根据历史表现。 ESG建议历史回顾用安全监视的一些个类型并且/或者cybersecurity智力补充分享,以便组织在真正的时间可能更好估计cyber供应链安全风险。

|

|

To assess the cybersecurity policies, processes, and controls with consistency, all IT vendor security audits should adhere to a formal, documented methodology. ESG research indicates that half of all critical infrastructure organizations conduct a formal security audit process in all cases, while the other half have some flexibility to deviate from formal IT vendor security audit processes on occasion (see Figure 11). It is worth noting that 57% of financial services organizations have a formal security audit process for IT vendors that must be followed in all cases, as opposed to 47% of organizations in other industries. This is another indication that financial services firms tend to have more advanced and stringent cybersecurity policies and processes than those from other industries.

|

估计cybersecurity政策、过程和控制以它供营商安全审计应该遵守正式的一贯性,所有,被提供的方法学。 ESG研究表明一半所有重要基础设施组织在所有的情况下举办一个正式安全审计过程,而另外一半有一些灵活性从正式偏离它供营商安全偶尔审计过程(参见图11)。 它值得注意到, 57%金融服务组织有一个正式安全审计过程为它必须在所有的情况下被跟随的供营商,与47%组织相对在其他产业。 这是金融服务企业比那些倾向于有先进的和更加严密的cybersecurity政策和过程从其他产业的另一个征兆。

|

|

IT vendor security audits involve data collection, analysis, evaluations, and final decision-making. From a scoring perspective, just over half (51%) of critical infrastructure organizations employ formal metrics/scorecards where IT vendors must attain a certain cybersecurity profile to qualify as an approved supplier. The remainder of critical infrastructure organizations have less stringent guidelines—32% have a formal vendor review process but no specific metrics for vendor qualification, while 16% conduct an informal review process (see Figure 12).

|

它供营商安全审计介入数据收集,分析、评估和最后的政策制定。 从计分的透视,刚好超过半数(51%)重要基础设施组织使用正式度规或计分卡,它供营商必须获得某一cybersecurity外形合格作为批准的供应商。 重要基础设施组织剩下的人没有较不严密指南32%有一个正式供营商回顾过程,但具体度规为供营商资格,而16%品行一个不拘形式的回顾过程(参见图12)。

|

|

Overall, ESG research indicates that many critical organizations are not doing enough due diligence with IT vendor cybersecurity audits. To minimize the risk of a cyber supply chain security incident, vendor audit best practices would have to include the following three steps:

|

总之, ESG研究表明许多重要组织不做着足够的适当努力以它供营商cybersecurity审计。 要使cyber供应链安全事件减到最小的风险,供营商审计最佳的实践将必须包括以下三步:

|

|

1. Organization always audits the internal security processes of strategic IT vendors.

|

1. 组织总验核内部安全过程的战略它供营商。

|

|

1. Organization uses a formal standard audit process for all IT vendor audits.

|

1. 组织为所有使用一个正式标准审计过程它供营商审计。

|

|

2. Organization employs formal metrics/scorecards where IT vendors must exceed a scoring threshold to qualify for IT purchasing approval.

|

2. 组织使用正式度规或计分卡,它必须超出计分的门限在它合格购买认同的供营商。

|

|

When ESG assessed critical infrastructure organizations through this series of IT vendor audit steps, the results were extremely distressing. For example, on average, only 14% of the total survey population adhered to all three best practice steps when auditing the security of their strategic infrastructure vendors (see Table 3). Since strategic infrastructure vendors are audited most often, it is safe to assume that less than 14% of the total survey population follows these best practices when auditing the security of software vendors, cloud service providers, professional services firms, and distributors.

|

当ESG通过这系列它估计了重要基础设施组织供营商审计步,结果是极端困厄的。 例如,平均,仅14%总勘测人口遵守了所有三最佳的实践步,当验核他们的战略基础设施供营商时安全(参见表3)。 因为战略基础设施供营商经常被验核,假设是安全的,少于14%总勘测人口跟随这些最佳的实践,当验核软件商,云彩服务提供者时安全,专业服务变牢固和经销商。

|

Table 3. Incidence of Best Practices for IT Vendor Security Audits

|

It is also worth noting that ESG data shows marginal improvements regarding IT vendor security auditing best practices in the last five years. In 2010, only 10% of critical infrastructure organizations followed all six best practice steps, while 14% do so in 2015. Clearly, there is still a lot of room for improvement.

|

它也是值得注意的ESG数据在最近五年显示少量的改善关于它验核最佳的实践的供营商安全。 2010年, 2015年,而14%如此做仅10%重要基础设施组织跟随全部六最佳的实践步。 清楚地,有很多室为改善。

|

|

Regardless of security audit deficiencies, many critical infrastructure organizations are somewhat bullish about their IT vendors’ security. On average, 41% of cybersecurity professionals rate all types of IT vendors as excellent in terms of their commitment to and communications about their internal security processes and procedures, led by strategic infrastructure vendors achieving an excellent rating from 49% of the cybersecurity professionals surveyed (see Figure 13).

|

不管安全审计缺乏,许多重要基础设施组织是有些看涨关于他们它供营商’安全。 平均, 41% cybersecurity专家对所有类型的它估计供营商如优秀根据他们的承诺对和通信关于他们的内部安全过程和规程,带领由达到一个优秀规定值的战略基础设施供营商从49% cybersecurity专家被勘测(参见图13)。

|

|

Critical infrastructure organizations gave their IT vendors more positive security ratings in 2015 compared with 2010. For example, only 19% of critical infrastructure organizations rated their strategic infrastructure vendors as excellent in 2010 compared with 49% in 2015. Many IT vendors have recognized the importance of building cybersecurity into products and processes during this timeframe and are much more forthcoming about their cybersecurity improvements. Furthermore, critical infrastructure organizations have increased the amount of vendor security due diligence over the last five years, leading to greater visibility and improved vendor ratings.

|

重要基础设施组织在2015给了他们它供营商更加正面的安全规定值比较2010年。 例如,在2015年仅19%重要基础设施组织对他们的战略基础设施供营商估计如优秀在2010比较49%。 许多它供营商认可了建立cybersecurity入产品和过程的重要性在这期限期间并且是much more即将到来关于他们的cybersecurity改善。 此外,重要基础设施组织增加了相当数量供营商安全适当努力在过去五年期间,导致更加伟大的可见性和被改进的供营商规定值。

|

|

The news isn’t all good as at least 12% of critical infrastructure organizations are only willing to give their IT vendors’ internal security processes and procedures a satisfactory, fair, or poor rating. ESG is especially concerned with ratings associated with resellers, VARs, and distributors since 24% of critical infrastructure organizations rate their internal security processes and procedures as satisfactory, fair, or poor. This is especially troubling since Figure 10 reveals that 18% of critical infrastructure organizations do not perform security audits on resellers, VARs, and distributors. Based upon all of this data, it appears that critical infrastructure organizations remain vulnerable to cybersecurity attacks (like supply chain interdiction) emanating from resellers, VARs, and distributors.

|

新闻不是所有好,因为至少12%重要基础设施组织只是愿意给他们它供营商’内部安全过程和规程令人满意,市场或者恶劣的规定值。 ESG与规定值特别是有关与转售者, VARs相关,并且经销商从24%重要基础设施组织对他们的内部安全过程估计和规程如令人满意,市场或者贫寒。 这是特别令人焦虑的,因为图10显露18%重要基础设施组织在转售者、VARs和经销商不执行安全审计。 基于所有这数据,看起来重要基础设施组织依然是脆弱到(象供应链禁止)发出从转售者、VARs和经销商的cybersecurity攻击。

|

|

IT hardware and software is often developed, tested, assembled, or manufactured in multiple countries with varying degrees of patent protection or legal oversight. Some of these countries are known “hot beds” of cybercrime or even state-sponsored cyber-espionage. Given these realities, one would think that critical infrastructure organizations would carefully trace the origins of the IT products purchased and used by their firms.

|

它硬件和软件在多个国家被开发,被测试,经常被装配或者被制造以不同程度专利保护或法律失察。 其中一些国家是知道的“热的床”计算机错误行为甚至政府支持的cyber间谍活动。 给出这些现实,你认为重要基础设施组织将仔细地追踪起源的它他们的企业购买和使用的产品。

|

|

ESG’s data suggests that most firms are at least somewhat certain about the geographic lineage of their IT assets (see Figure 14). It should also be noted that there have been measurable improvements in this area as 41% of critical infrastructure organizations are very confident that they know the country in which their IT hardware and software products were originally developed and/or manufactured compared with only 24% in 2010. Once again, ESG attributes this progress to improvements in IT vendor security due diligence, greater supply chain security oversight within the IT vendor community, and increased overall cyber supply chain security awareness across the entire cybersecurity community over the past five years.

|

ESG的数据建议多数企业至少有些肯定关于地理后裔他们它财产(参见图14)。 应该也注意到它,有可测量的改善在这个区域,因为41%重要基础设施组织非常确信他们知道他们它硬件和软件产品只最初被开发并且/或者被制造比较24%的国家在2010年。 再次, ESG在之内归因于这进展在它的改善供营商安全适当努力、更加巨大的供应链安全失察它供营商社区和增加的整体cyber供应链安全了悟横跨整个cybersecurity社区在过去五年。

|

|

While cybersecurity professionals gave positive ratings to their IT vendors’ security and are fairly confident about the origins of their IT hardware and software, they remain vulnerable because of insecure hardware and software that somehow circumvent IT vendor security audits, fall through the cracks, and end up in production environments. In fact, the majority (58%) of critical infrastructure organizations admit that they use insecure products and/or services that are a cause for concern (see Figure 15). One IT product or service vulnerability could represent the proverbial “weak link” that leads to a cyber-attack on the power grid, ATM network, or water supply.

|

当cybersecurity专家给了正面规定值他们它供营商’安全并且是相当确信关于起源的他们它硬件和软件时,他们保持脆弱由于不安全的硬件和软件在生产环境里莫名其妙地徊避它供营商安全审计,遭遗漏,并且结果。 实际上,多数(58%)重要基础设施组织承认他们使用是令人担心的事的不安全的产品和服务(参见图15)。 一那在功率网格导致cyber攻击的它产品或服务弱点可能代表谚语的“弱链接”, ATM网络或者给水。

|

Cyber Supply Chain Security and Software Assurance

|

Cyber供应链安全和软件保证

|

|

Software assurance is another key tenet of cyber supply chain security as it addresses the risks associated with a cybersecurity attack targeting business software. The U.S. Department of Defense defines software assurance as:

|

因为它演讲风险与瞄准商业软件的cybersecurity攻击相关软件保证是cyber供应链安全另一条关键原则。 美国。 国防部定义了软件保证如下:

|

|

“The level of confidence that software is free from vulnerabilities, either intentionally designed into the software or accidentally inserted at any time during its lifecycle, and that the software functions in the intended manner.”

|

在它的生命周期期间, “软件故意地是从弱点解脱,信心的水平设计了入软件或任何时候偶然地插入了,并且软件起作用以意欲的方式”。

|

|

Critical infrastructure organizations tend to have sophisticated IT requirements, so it comes as no surprise that 40% of organizations surveyed develop a significant amount of software for internal use while another 41% of organizations develop a moderate amount of software for internal use (see Figure 16).

|

重要基础设施组织倾向于使它复杂要求,因此它来作为被勘测的40%组织开发相当数量软件为内部使用的没有惊奇,当另外41%组织开发一个适量软件为内部使用时(参见图16)。

|

|

Software vulnerabilities continue to represent a major threat vector for cyber-attacks. For example, the 2015 Verizon Data Breach and Investigations Report found that web application attacks accounted for 9.4% of incident classification patterns within the confirmed data breaches. Since any poorly written, insecure software could represent a significant risk to business operations, ESG asked respondents to rate their organizations on the security of their internally developed software. The results vary greatly: 47% of respondents say that they are very confident in the security of their organization’s internally developed software, but 43% are only somewhat confident and another 8% remain neutral (see Figure 17).

|

软件弱点继续代表主要威胁传染媒介为cyber攻击。 例如, 2015年Verizon数据突破口和调查报告发现Web应用程序攻击在被证实的数据突破口之内占9.4%事件分类样式。 从不足书面的其中任一,不安全的软件可能代表一种重大风险到经营活动, ESG在他们的内部被开发的软件安全要求应答者对他们的组织估计。 结果很大地变化: 47%应答者认为他们对他们的组织的内部被开发的软件安全是非常确信,但43%只有些确信,并且另外8%保持中立(参见图17)。

|

|

There is a slight increase in the confidence level over the past five years as 36% of cybersecurity professionals working at critical infrastructure organizations were very confident in the security of their organization’s internally developed software in 2010 compared with 47% today. But this is a marginal improvement at best.

|

有在信心的轻微的增量在过去五年作为36%工作在重要基础设施组织的cybersecurity专家对他们的组织的内部被开发的软件安全是非常确信在2010今天比较47%。 但这是少量的改善最好。

|

|

To assess software security more objectively, ESG asked respondents whether their organization ever experienced a security incident directly related to the compromise of internally developed software. As it turns out, one-third of critical infrastructure organizations have experienced one or several security incidents that were directly related to the compromise of internally developed software (see Figure 18).

|

更加客观地要估计软件安全, ESG请求应答者他们的组织是否体验了安全事件直接地与内部被开发的软件有关妥协。 当它结果,重要基础设施组织的三分之一体验了直接地与内部被开发的软件有关妥协的一个或几个安全事件(参见图18)。

|

|

From an industry perspective, 39% of financial services firms have experienced a security incident directly related to the compromise of internally developed software compared with 30% of organizations from other critical infrastructure industries. This happens in spite of the fact that financial services tend to have advanced cybersecurity skills and adequate cybersecurity resources. ESG finds this data particularly troubling since a cyber-attack on a major U.S. bank could disrupt the domestic financial system, impact global markets, and cause massive consumer panic.

|

从产业透视, 39%金融服务企业体验了安全事件直接地与内部被开发的软件有关妥协比较30%组织从其他重要基础设施产业。 这发生金融服务即使倾向于推进了cybersecurity技能和充分cybersecurity资源。 因为cyber攻击在主要美国, ESG发现这数据特别令人焦虑。 银行能打乱国内财政系统,冲击全球性市场和导致巨型的消费者恐慌。

|

|

Critical infrastructure organizations recognize the risks associated with insecure software and are actively employing a variety of security controls and software assurance programs. The most popular of these is also the easiest to implement as 51% of the organizations surveyed have deployed application firewalls to block application-layer cyber-attacks such as SQL injections and cross-site scripting (XSS). In addition to deploying application firewalls, about half of the critical infrastructure organizations surveyed also include security testing tools as part of their software development processes, measuring their software security against publicly available standards, providing secure software development training to internal developers, and adopting secure software development lifecycle processes (see Figure 19). Of course, many organizations are engaged in several of these activities simultaneously in order to bolster the security of their homegrown software.

|

重要基础设施组织认可风险与不安全的软件相关和活跃地使用各种各样的安全控制和软件保证节目。 最普遍这些也是最容易实施,因为被勘测的51%组织部署应用防火墙阻拦应用层数cyber攻击例如SQL射入和十字架站点写电影脚本(XSS)。 作为他们的软件开发过程一部分,除部署的应用防火墙之外,大约也被勘测的重要基础设施组织的半包括安全测试工具,措施他们的软件安全反对公开地可利用的标准,提供训练给内部开发商和采取安全软件开发生命周期过程的安全软件开发(参见图19)。 当然,许多组织同时参与几个这些之中活动为了支持他们的家庭产生的软件安全。

|

|

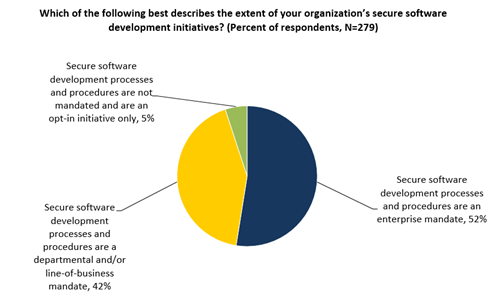

Secure software development programs are certainly a step in the right direction, but software assurance effectiveness is a function of two factors: the types of programs employed and the consistency of these programs. ESG research reveals that just over half of critical infrastructure organizations treat secure software development processes and procedures as an enterprise mandate, so it’s likely that these firms have a consistent secure software development methodology across the organization.

|

安全软件开发节目一定是步在正确的方向,但软件保证有效率是二个因素的作用: 被使用的节目的种类和这些节目一贯性。 ESG研究显露刚好超过半数重要基础设施组织治疗安全软件开发过程和规程作为企业命令,因此它是可能的这些企业有一个一致的安全软件开发方法横跨组织。

|

|

Alternatively, 42% of the critical infrastructure organizations surveyed implement secure software development processes and procedures as departmental or line-of-business mandates (see Figure 20). Decentralized software security processes like these can lead to tremendous variability where some departments institute strong software assurance programs while others do not. Furthermore, secure software development programs can vary throughout the enterprise where one department provides training and formal processes while another simply deploys an application firewall. As the old saying goes, “One bad apple can spoil the whole bunch”—a single department that deploys insecure internally developed software can open the door to damaging cyber-attacks that impact the entire enterprise and disrupt critical infrastructure services like food distribution, health care, or telecommunications.

|

二者择一地,被勘测的42%重要基础设施组织实施安全软件开发过程和规程作为部门或线事务命令(参见图20)。 分散的软件安全过程象这些可能导致巨大可变性,有些部门设立强的软件保证节目,而其他不。 此外,安全软件开发节目可能变化在企业中,一个部门提供训练和正式过程,当另简单地部署应用防火墙时。 当老说法是, “一个坏苹果可能损坏整体束” -部署不安全的内部被开发的软件可能对损坏打开门cyber攻击冲击整个企业的一个唯一部门和打乱重要基础设施服务象食品配给、医疗保健或者电信。

|

|

Critical infrastructure organizations are implementing secure software development programs for a number of reasons, including adhering to general cybersecurity best practices (63%), meeting regulatory compliance mandates (55%), and even lowering costs by fixing software security bugs in the development process (see Figure 21).

|

重要基础设施组织在发展过程中实施安全软件开发节目为一定数量的原因,包括遵守一般cybersecurity最佳的实践(63%),遇见管理服从命令(55%)和降低的费用通过修理软件安全臭虫(参见图21)。

|

|

It is also worth noting that 27% of critical infrastructure organizations are establishing secure software development programs in anticipation of new legislation. These organizations may be thinking in terms of the NIST cybersecurity framework (CSF) first introduced in February 2014. Although compliance with the CSF is voluntary today, it may evolve into a common risk management and regulatory compliance standard that supersedes other government and industry regulations like FISMA, GLBA, HIPAA, and PCI-DSS in the future. Furthermore, the CSF may also become a standard for benchmarking IT risk as part of cyber insurance underwriting and may be used to determine organizations’ insurance premiums. Given these possibilities, critical infrastructure organizations would be wise to consult the CSF, assess CSF recommendations for software security, and use the CSF to guide their software security processes and controls wherever possible.

|

它也是值得注意的27%重要基础设施组织建立安全软件开发节目预期新的立法。 这些组织也许认为根据在2014年2月(CSF)首先介绍的NIST cybersecurity框架。 虽然遵照CSF是义务今天,它也许转变成在将来代替其他政府和产业章程象FISMA、GLBA、HIPAA和PCI-DSS的一个共同的风险管理和管理服从标准。 此外, CSF也许也成为一个标准为基准点它风险作为cyber保险一部分认购并且也许使用确定组织’保险费。 给出这些可能性,重要基础设施组织是明智咨询CSF,估计对软件安全的CSF推荐和使用CSF在任何可能的情况下引导他们的软件安全过程和控制。

|

|

Aside from the ongoing software security actions taken today, critical infrastructure organizations also have future plans—28% plan to include specific security testing tools as part of software development, 25% will add web application firewalls to their infrastructure, and 24% will hire developers and development managers with secure software development skills (see Figure 22). These ambitious plans indicate that CISOs recognize their software development security deficiencies and are taking precautions in order to mitigate risk.

|

除今天采取的持续的软件安全行动之外,重要基础设施组织也有未来计划28%计划包括具体安全测试工具作为软件开发一部分, 25%将增加Web应用程序防火墙到他们的基础设施,并且24%将雇用开发商和发展经理以安全软件开发技能(参见图22)。 这些雄心勃勃的计划表明CISOs认可他们的软件开发安全缺乏和采取防备措施为了缓和风险。

|

|

Some software development, maintenance, and testing activities are often outsourced to third-party contractors and service providers. This is the case at half of the critical infrastructure organizations that participated in this ESG research survey (see Figure 23).

|

一些软件开发、维护和测试的活动经常外购对第三方承包商和服务提供者。 这是实际情形在参加这份ESG研究调查重要基础设施组织的一半(参见图23)。

|

|

As part of these relationships, many critical infrastructure organizations place specific cybersecurity contractual requirements on third-party software development partners. For example, 43% mandate security testing as part of the acceptance process, 41% demand background checks on third-party software developers, and 41% review software development projects for security vulnerabilities (see Figure 24).

|

作为这些关系一部分,许多重要基础设施组织在第三方软件开发伙伴安置具体cybersecurity契约要求。 例如, 43%测试作为采纳过程、41%需求背景检查在第三方软件开发商和41%回顾软件开发项目一部分的命令安全对于安全漏洞(参见图24)。

|

Cybersecurity, Critical Infrastructure Security Professionals, and the U.S. Federal Government

|

Cybersecurity、重要基础设施安全专家和美国。 联邦政府

|

|

ESG research indicates a pattern of persistent cybersecurity incidents at U.S. critical infrastructure organizations over the past few years. Furthermore, security professionals working in critical infrastructure industries believe that the cyber-threat landscape is more dangerous today than it was two years ago.

|

ESG研究表明坚持cybersecurity事件的样式在美国。 重要基础设施组织在过去几年。 此外,工作在重要基础设施产业的安全专家相信cyber威胁风景比它二年前是更加危险的今天。

|

|

To address these issues, President Obama and various other elected officials proposed several cybersecurity programs such as the NIST cybersecurity framework and an increase in threat intelligence sharing between critical infrastructure organizations and federal intelligence and law enforcement agencies. Of course, federal cybersecurity discussions are nothing new. Recognizing a national security vulnerability, President Clinton first addressed critical infrastructure protection (CIP) with Presidential Decision Directive 63 (PDD-63) in 1998. Soon thereafter, Deputy Defense Secretary John Hamre cautioned the U.S. Congress about CIP by warning of a potential “cyber Pearl Harbor.” Hamre stated that a devastating cyber-attack, “… is not going to be against Navy ships sitting in a Navy shipyard. It is going to be against commercial infrastructure.”

|

要论及这些问题, Obama总统和各种各样的当选行政官提出几个cybersecurity节目例如NIST cybersecurity框架和在分享在重要基础设施组织和联邦智力和执法机构之间的威胁智力的增量。 当然,联邦cybersecurity讨论是没有新东西。 认可一个国家安全弱点, 1998年克林顿总统首先演讲了重要基础设施保护(CIP)以总统决定方针63 (PDD-63)。 紧接着,代理国防部长约翰Hamre警告了美国。 国会关于CIP由潜在的“cyber珍珠港的警告”。 Hamre阐明,毁灭cyber攻击, “…不反对坐在海军造船厂的军舰。 它反对商业基础设施”。

|

|

Security professionals working at critical infrastructure industries have been directly or indirectly engaged with U.S. Federal Government cybersecurity programs and initiatives through several Presidential administrations. Given this lengthy timeframe, ESG wondered whether these security professionals truly understood the U.S. government’s cybersecurity strategy. As seen in Figure 31, the results are mixed at best. One could easily conclude that the data resembles a normal curve where the majority of respondents believe that the U.S. government’s cybersecurity strategy is somewhat clear while the rest of the survey population is distributed between those who believe that the U.S. government’s cybersecurity strategy is very clear and those who say it is unclear.

|

工作在重要基础设施产业的安全专家直接地是或间接地美国与$$4相啮。 联邦政府cybersecurity节目和主动性通过几总统管理。 给出这长的期限, ESG想知道这些安全专家是否真实地了解美国。 政府的cybersecurity战略。 如被看见在表31,结果被混合最好。 你可能容易地认为,数据类似一条常态曲线,多数应答者相信美国。 政府的cybersecurity战略是有些清楚的,当勘测人口的其余被分布在相信美国的那些人之间时。 政府的cybersecurity战略是非常清楚的,并且认为它的那些人是不明的。

|

|

ESG views the results somewhat differently. In spite of over 20 years of U.S. federal cybersecurity discussions, many security professionals remain unclear about what the government plans to do in this space. Clearly, the U.S. Federal Government needs to clarify its mission, its objectives, and its timeline with cybersecurity professionals to gain their trust and enlist their support for public/private programs.

|

ESG有些不同地观看结果。 竟管在美国的20年期间。 联邦cybersecurity讨论,许多安全专家依然是不明关于什么要做的政府计划在这空间。 清楚地,美国联邦政府需要澄清它的使命、它的宗旨和它的时间安排与cybersecurity专家获取他们的信任和征求他们的为公开或私有节目。

|

|

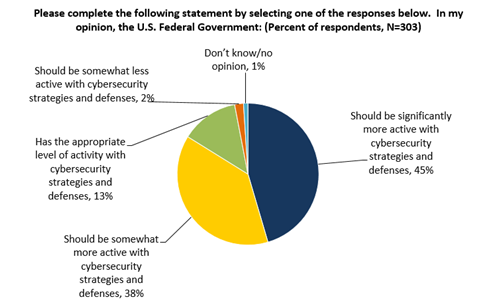

While critical infrastructure security professionals may be uncertain about the U.S. Federal Government’s strategy, they would also like to see Washington become more engaged. Nearly half (45%) of critical infrastructure organizations believe that the U.S. Federal Government should be significantly more active with cybersecurity strategies and defenses while 38% believe that the U.S. Federal Government should be somewhat more active with cybersecurity strategies and defenses (see Figure 32).

|

当重要时基础设施安全专家也许是不定的关于美国。 联邦政府的战略,他们也希望看华盛顿变得参与。 近一半(45%)重要基础设施组织相信美国。 当38%相信美国时,联邦政府应该是更激活与cybersecurity战略和防御。 联邦政府应该是稍微活跃与cybersecurity战略和防御(参见图32)。

|

|

Finally, ESG asked the entire survey population of security professionals what types of cybersecurity actions the U.S. Federal Government should take. Nearly half (47%) believe that Washington should create better ways to share security information with the private sector. This aligns well with President Obama’s executive order urging companies to share cybersecurity threat information with the U.S. Federal Government and one another. Cybersecurity professionals have numerous other suggestions as well. Some of these could be considered government cybersecurity enticements. For example, 37% suggest more funding for cybersecurity education programs while 36% would like more incentives like tax breaks or matching funds for organizations that invest in cybersecurity. Alternatively, many cybersecurity professionals recommend more punitive or legislative measures—44% believe that the U.S. Federal Government should create a “black list” of vendors with poor product security (i.e., the cybersecurity equivalent of a scarlet letter), 40% say that the U.S. Federal Government should limit its IT purchasing to vendors that display a superior level of security, and 40% endorse more stringent regulations like PCI DSS or enacting laws with higher fines for data breaches (see Figure 33).

|

终于, ESG要求安全专家的整个勘测人口什么样的cybersecurity行动美国。 联邦政府应该采取。 (47%)几乎半相信华盛顿应该创造更好的方式与私人部门分享担保信息。 这与敦促公司的Obama总统的行政命令很好排列与美国分享cybersecurity威胁信息。 联邦政府和。 Cybersecurity专家有许多其他建议。 其中一些能被认为政府cybersecurity诱惑。 例如, 37%建议更多资助为cybersecurity教育规划,当36%将想要更多刺激象减税或吻合配调为在cybersecurity投资的组织时。 二者择一地,许多cybersecurity专家推荐更加惩罚或立法措施44%相信美国。 联邦政府应该建立“黑名单”供营商以恶劣的产品安全(即,红A字的cybersecurity等值),美国的40%言。 联邦政府应该限制它购买对显示安全的一个优越水平的供营商的它,并且40%支持更加严密的章程象PCI DSS或颁布法律与更高的罚款为数据破坏(参见图33)。

|

|

Of course, it’s unrealistic to expect draconian cybersecurity policies and regulations from Washington, but the ESG data presents a clear picture: Cybersecurity professionals would like to see the U.S. Federal Government use its visibility, influence, and purchasing power to produce cybersecurity “carrots” and “sticks.” In other words, Washington should be willing to reward IT vendors and critical infrastructure organizations that meet strong cybersecurity metrics and punish those that cannot adhere to this type of standard.

|

当然,期望严厉的cybersecurity政策和章程从华盛顿是不切实际的,但ESG数据提出一张清楚的图片: Cybersecurity专家希望看美国联邦政府用途它的可见性、影响和购买力生产cybersecurity “红萝卜”和“棍子”。 换句话说,华盛顿应该是愿意奖励它遇见强的cybersecurity度规的供营商和重要基础设施组织并且惩罚不可能遵守标准的这个类型的那些。

|

|

|