|

|

Research Findings

The Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity Landscape

Today’s Outlook on Cybersecurity Threats More Bleak than in 2013

Defending against cyber-attacks represents a perpetual battle for critical infrastructure organizations facing an increasingly dangerous threat landscape. In fact, 31% of security professionals working at critical infrastructure organizations believe that the threat landscape today is much worse than it was two years ago, while another 36% say it is somewhat worse (see Figure 1).

It is interesting to note that ESG asked this same question in its 2010 research project,1 and it produced strikingly similar results—68% of respondents said that the threat landscape was worse in 2010 compared with 2008. Clearly, the threat landscape is getting more hazardous on an annual basis with no letup in sight. ESG finds this data particularly troubling. U.S. citizens depend upon critical infrastructure organizations for the basic necessities of modern society like food, water, fuel, and telecommunications services. Given the increasingly dangerous threat landscape, critical infrastructure organizations are tasked with maintaining important everyday services and defending their networks from a growing army of cyber-criminals, hacktivists, and nation state actors.

Note1: Source: ESG Research Report, Assessing Cyber Supply Chain Security Vulnerabilities Within the U.S. Critical Infrastructure, November 2010.

These beliefs about the increasingly dangerous threat landscape go beyond opinions alone as many critical infrastructure organizations face constant cyber-attacks. A majority (68%) of critical infrastructure organizations experienced a security incident over the past two years, with nearly one-third (31%) experiencing a system compromise as a result of a generic attack (i.e., virus, Trojan, etc.) brought in by a user’s system, 26% reporting a data breach due to lost/stolen equipment, and 25% of critical infrastructure organizations suffering some type of insider attack (see Figure 2). Alarmingly, more than half (53%) of critical infrastructure organizations have dealt with at least two of these security incidents since 2013.

Security incidents always come with ramifications associated with time and money. For example, nearly half (47%) of cybersecurity professionals working at critical infrastructure organizations claim that security incidents required significant IT time/personnel for remediation. While this places an unexpected burden on IT and cybersecurity groups, other consequences related to security incidents were far more ominous—36% say that security incidents led to the disruption of a critical business process or business operations, 36% claim that security incidents resulted in the disruption of business applications or IT systems availability, and 32% report that security incidents led to a breach of confidential data (see Figure 3).

This data should be cause for concern since a successful cyber-attack on critical infrastructure organizations’ applications and processes could result in the disruption of electrical power, health care services, or the distribution of food. Thus, these issues could have a devastating impact on U.S. citizens and national security.

Cybersecurity at Critical Infrastructure Organizations

Do critical infrastructure organizations believe they have the right cybersecurity policies, processes, skills, and technologies to address the increasingly dangerous threat landscape? The results of that inquiry are mixed at best. On the positive side, 37% rate their organizations’ cybersecurity policies, processes, and technologies as excellent and capable of addressing almost all of today’s threats. It is worth noting that the overall ratings have improved since 2010 (see Table 1). While this improvement is noteworthy, 10% of critical infrastructure security professionals still rate their organization as fair or poor.

Being able to deal with most threats may be an improvement from 2010, but it is still not enough. This is especially true given the fact that the threat landscape has grown more difficult at the same time. Critical infrastructure organizations are making progress, but defensive measures are not progressing at the same pace as the offensive capabilities of today’s cyber-adversaries and this risk gap leaves all U.S. citizens vulnerable.

Table 1. Respondents Rate Organization’s Cybersecurity Policies

Given the national security implications of critical infrastructure, it is not surprising that cybersecurity risk has become an increasingly important board room issue over the past five years. Nearly half (45%) of cybersecurity professionals today rate their organization’s executive management team as excellent, while only 25% rated them as highly in 2010 (see Table 2). Alternatively, 10% rate the executive management team’s cybersecurity commitment as fair or poor in 2015, where 23% rated them so in 2010. These results are somewhat expected given the visible and damaging data breaches of the past few years. Critical infrastructure cybersecurity is also top of mind in Washington with legislators, civilian agencies, and the executive branch. For example, the 2014 National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) cybersecurity framework (CSF) was driven by an executive order and is intended to help critical infrastructure organizations measure and manage cyber-risk more effectively. As a result of all of this cybersecurity activity, corporate boards are much more engaged in cybersecurity than they were in the past, but whether they are doing enough or investing in the right areas is still questionable.

Table 2. Respondents Rate Organization’s Executive Management Team with Regard to Cybersecurity Initiatives

Critical infrastructure organizations are modifying their cybersecurity strategies for a number of reasons. For example, 37% say that their organization’s infosec strategy is driven by the need to support new IT initiatives with strong security best practices. This likely refers to IT projects for process automation that include Internet of Things (IoT) technologies. IoT projects can bolster productivity, but they also introduce new vulnerabilities and thus the need for additional security controls. Furthermore, 37% point to protecting sensitive customer data confidentiality and integrity, and 36% call out the need to protect internal data confidentiality and integrity (see Figure 4). These are certainly worthwhile goals, but ESG was surprised that only 22% of critical infrastructures say that their information security strategy is being driven by preventing/detecting targeted attacks and sophisticated malware threats. After all, 67% of security professionals believe that the threat landscape is more dangerous today than it was two years ago, and 68% of organizations have suffered at least one security incident over the past two years. Since critical infrastructure organizations are under constant attack, ESG feels strongly that CISOs in these organizations should be assessing whether they are doing enough to prevent, detect, and respond to modern cyber-attacks.

Cyber Supply Chain Security

Like many other areas of cybersecurity, cyber supply chain security is growing increasingly cumbersome. In fact, 60% of security professionals say that cyber supply chain security has become either much more difficult (17%) or somewhat more difficult (43%) over the last two years (see Figure 5).

Why has cyber supply chain security become more difficult? Forty-four percent claim that their organizations have implemented new types of IT initiatives (i.e., cloud computing, mobile applications, IoT, big data analytics projects, etc.), which have increased the cyber supply chain attack surface; 39% say that their organization has more IT suppliers than it did two years ago; and 36% state that their organization has consolidated IT and operational technology security, which has increased infosec complexity (see Figure 6).

This data is indicative of the state of IT today. The fact is that IT applications, infrastructure, and products are evolving at an increasing pace, driving dynamic changes on a constant basis and increasing the overall cyber supply chain attack surface. Over-burdened CISOs and infosec staff find it difficult to keep up with dynamic cyber supply chain security changes, leading to escalating risks.

Cyber Supply Chain Security and Information Technology

Cybersecurity protection begins with a highly secure IT infrastructure. Networking equipment, servers, endpoints, and IoT devices should be “hardened” before they are deployed on production networks. Access to all IT systems must adhere to the principle of “least privilege” and be safeguarded with role-based access controls that are audited on a continuous or regular basis. IT administration must be segmented through “separation of duties.” Networks must be scanned regularly and software patches applied rapidly. All security controls must be monitored constantly.

These principles are often applied to internal applications, networks, and systems but may not be as stringent with regard to the extensive network of IT suppliers, service providers, business partners, contractors, and customers that make up the cyber supply chain. As a review, the cyber supply chain is defined as:

The entire set of key actors involved with/using cyber infrastructure: system end-users, policy makers, acquisition specialists, system integrators, network providers, and software/hardware suppliers. The organizational and process-level interactions between these constituencies are used to plan, build, manage, maintain, and defend the cyber infrastructure.”

To explore the many facets of cyber supply chain security, this report examines:

The relationships between critical infrastructure organizations and their IT vendors (i.e., hardware, software, and services suppliers as well as system integrators, channel partners, and distributors).

The security processes and oversight applied to critical infrastructure organizations’ software that is produced by internal developers and third parties.

Cybersecurity processes and controls in instances where critical infrastructure organizations are either providing third parties (i.e., suppliers, customers, and business partners) with access to IT applications and services, or are consuming IT applications and services provided by third parties (note: throughout this report, this is often referred to as “external IT”).

Cyber Supply Chain Security and IT Suppliers

Cybersecurity product vendors, service providers, and resellers are an essential part of the overall cyber supply chain. Accordingly, their cybersecurity policies and processes can have a profound downstream impact on their customers, their customers’ customers, and so on. Given this situation, critical infrastructure organizations often include cybersecurity considerations when making IT procurement decisions.

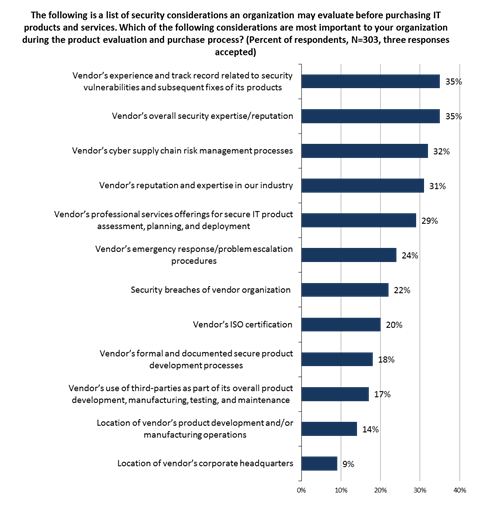

Just what types of cybersecurity considerations are most important? More than one-third (35%) of organizations consider their vendors’ experience and track record related to security vulnerabilities and subsequent fixes. In other words, critical infrastructure organizations are judging vendors by the quality of their software and their responsiveness in fixing software vulnerabilities when they do arise. Another 35% consider their vendors’ overall security expertise and reputation. Close behind, 32% consider their vendors’ cyber supply chain risk management processes, while 31% contemplate their vendors’ reputation and industry expertise (see Figure 7).

Clearly, critical infrastructure organizations have a number of cybersecurity considerations regarding their IT vendors, but many of these concerns, such as vendor reputation and expertise, remain subjective. To counterbalance these soft considerations, CISOs should really establish a list of objective metrics such as the number of CVEs associated with specific ISV applications and the average timeframe between vulnerability disclosure and security patch releases. These types of metrics can be helpful when comparing one IT vendor’s security proficiency against another’s.

Cyber supply chain security best practices dictate that organizations assess the security processes, procedures, and technology safeguards used by all of their IT suppliers. In order to measure the cybersecurity practices of IT vendors, some critical infrastructure organizations conduct proactive security audits of cloud service providers, software providers, hardware manufacturers, professional services vendors that install and customize IT systems, and VARs/distributors that deliver IT equipment and/or services.

Are these security audits standard practice? ESG research reveals mixed results. On average, just under 50% of critical infrastructure organizations always audit all types of IT suppliers, a marked improvement from 2010 when 28% of critical infrastructure organizations always audited their IT suppliers. Nevertheless, there is still plenty of room for improvement. For example, 18% of organizations do not audit the security processes and procedures of resellers, VARs, and distributors at present. As the Snowden incident indicates, these IT distribution specialists can be used for supply chain interdiction for introducing malicious code, firmware, or backdoors into IT equipment to conduct a targeted attack or industrial espionage (see Figure 8).

IT vendor security audits appear to be a shared responsibility with the cybersecurity team playing a supporting role. General IT management has some responsibility for assessing IT vendor security at two-thirds (67%) of organizations, while the cybersecurity team is responsible in just over half (51%) of organizations (see Figure 9).

These results are somewhat curious. After all, why wouldn’t the cybersecurity team be responsible for IT vendor security audits in some capacity? Perhaps some organizations view IT vendor security audits as a formality, part of the procurement team’s responsibility, or address IT vendor security audits with standard “checkbox” paperwork alone. Regardless of the reason, IT vendor security audits will provide marginal value without hands-on cybersecurity oversight throughout the process.

IT vendor security audits vary widely in terms of breadth and depth, so ESG wanted some insight into the most common mechanisms used as part of the audit process. Just over half (54%) of organizations conduct a hands-on review of their vendors’ security history; 52% review documentation, processes, security metrics, and personnel related to their vendors’ cyber supply chain security processes; and 51% review their vendors’ internal security audits (see Figure 10).

Of course, many organizations include several of these mechanisms as part of their IT vendor security audits to get a more comprehensive perspective. Nevertheless, many of these audit considerations are based upon historical performance. ESG suggests that historical reviews be supplemented with some type of security monitoring and/or cybersecurity intelligence sharing so that organizations can better assess cyber supply chain security risks in real time.

To assess the cybersecurity policies, processes, and controls with consistency, all IT vendor security audits should adhere to a formal, documented methodology. ESG research indicates that half of all critical infrastructure organizations conduct a formal security audit process in all cases, while the other half have some flexibility to deviate from formal IT vendor security audit processes on occasion (see Figure 11). It is worth noting that 57% of financial services organizations have a formal security audit process for IT vendors that must be followed in all cases, as opposed to 47% of organizations in other industries. This is another indication that financial services firms tend to have more advanced and stringent cybersecurity policies and processes than those from other industries.

IT vendor security audits involve data collection, analysis, evaluations, and final decision-making. From a scoring perspective, just over half (51%) of critical infrastructure organizations employ formal metrics/scorecards where IT vendors must attain a certain cybersecurity profile to qualify as an approved supplier. The remainder of critical infrastructure organizations have less stringent guidelines—32% have a formal vendor review process but no specific metrics for vendor qualification, while 16% conduct an informal review process (see Figure 12).

Overall, ESG research indicates that many critical organizations are not doing enough due diligence with IT vendor cybersecurity audits. To minimize the risk of a cyber supply chain security incident, vendor audit best practices would have to include the following three steps:

1. Organization always audits the internal security processes of strategic IT vendors.

1. Organization uses a formal standard audit process for all IT vendor audits.

2. Organization employs formal metrics/scorecards where IT vendors must exceed a scoring threshold to qualify for IT purchasing approval.

When ESG assessed critical infrastructure organizations through this series of IT vendor audit steps, the results were extremely distressing. For example, on average, only 14% of the total survey population adhered to all three best practice steps when auditing the security of their strategic infrastructure vendors (see Table 3). Since strategic infrastructure vendors are audited most often, it is safe to assume that less than 14% of the total survey population follows these best practices when auditing the security of software vendors, cloud service providers, professional services firms, and distributors.

Table 3. Incidence of Best Practices for IT Vendor Security Audits

It is also worth noting that ESG data shows marginal improvements regarding IT vendor security auditing best practices in the last five years. In 2010, only 10% of critical infrastructure organizations followed all six best practice steps, while 14% do so in 2015. Clearly, there is still a lot of room for improvement.

Regardless of security audit deficiencies, many critical infrastructure organizations are somewhat bullish about their IT vendors’ security. On average, 41% of cybersecurity professionals rate all types of IT vendors as excellent in terms of their commitment to and communications about their internal security processes and procedures, led by strategic infrastructure vendors achieving an excellent rating from 49% of the cybersecurity professionals surveyed (see Figure 13).

Critical infrastructure organizations gave their IT vendors more positive security ratings in 2015 compared with 2010. For example, only 19% of critical infrastructure organizations rated their strategic infrastructure vendors as excellent in 2010 compared with 49% in 2015. Many IT vendors have recognized the importance of building cybersecurity into products and processes during this timeframe and are much more forthcoming about their cybersecurity improvements. Furthermore, critical infrastructure organizations have increased the amount of vendor security due diligence over the last five years, leading to greater visibility and improved vendor ratings.

The news isn’t all good as at least 12% of critical infrastructure organizations are only willing to give their IT vendors’ internal security processes and procedures a satisfactory, fair, or poor rating. ESG is especially concerned with ratings associated with resellers, VARs, and distributors since 24% of critical infrastructure organizations rate their internal security processes and procedures as satisfactory, fair, or poor. This is especially troubling since Figure 10 reveals that 18% of critical infrastructure organizations do not perform security audits on resellers, VARs, and distributors. Based upon all of this data, it appears that critical infrastructure organizations remain vulnerable to cybersecurity attacks (like supply chain interdiction) emanating from resellers, VARs, and distributors.

IT hardware and software is often developed, tested, assembled, or manufactured in multiple countries with varying degrees of patent protection or legal oversight. Some of these countries are known “hot beds” of cybercrime or even state-sponsored cyber-espionage. Given these realities, one would think that critical infrastructure organizations would carefully trace the origins of the IT products purchased and used by their firms.

ESG’s data suggests that most firms are at least somewhat certain about the geographic lineage of their IT assets (see Figure 14). It should also be noted that there have been measurable improvements in this area as 41% of critical infrastructure organizations are very confident that they know the country in which their IT hardware and software products were originally developed and/or manufactured compared with only 24% in 2010. Once again, ESG attributes this progress to improvements in IT vendor security due diligence, greater supply chain security oversight within the IT vendor community, and increased overall cyber supply chain security awareness across the entire cybersecurity community over the past five years.

While cybersecurity professionals gave positive ratings to their IT vendors’ security and are fairly confident about the origins of their IT hardware and software, they remain vulnerable because of insecure hardware and software that somehow circumvent IT vendor security audits, fall through the cracks, and end up in production environments. In fact, the majority (58%) of critical infrastructure organizations admit that they use insecure products and/or services that are a cause for concern (see Figure 15). One IT product or service vulnerability could represent the proverbial “weak link” that leads to a cyber-attack on the power grid, ATM network, or water supply.

Cyber Supply Chain Security and Software Assurance

Software assurance is another key tenet of cyber supply chain security as it addresses the risks associated with a cybersecurity attack targeting business software. The U.S. Department of Defense defines software assurance as:

“The level of confidence that software is free from vulnerabilities, either intentionally designed into the software or accidentally inserted at any time during its lifecycle, and that the software functions in the intended manner.”

Critical infrastructure organizations tend to have sophisticated IT requirements, so it comes as no surprise that 40% of organizations surveyed develop a significant amount of software for internal use while another 41% of organizations develop a moderate amount of software for internal use (see Figure 16).

Software vulnerabilities continue to represent a major threat vector for cyber-attacks. For example, the 2015 Verizon Data Breach and Investigations Report found that web application attacks accounted for 9.4% of incident classification patterns within the confirmed data breaches. Since any poorly written, insecure software could represent a significant risk to business operations, ESG asked respondents to rate their organizations on the security of their internally developed software. The results vary greatly: 47% of respondents say that they are very confident in the security of their organization’s internally developed software, but 43% are only somewhat confident and another 8% remain neutral (see Figure 17).

There is a slight increase in the confidence level over the past five years as 36% of cybersecurity professionals working at critical infrastructure organizations were very confident in the security of their organization’s internally developed software in 2010 compared with 47% today. But this is a marginal improvement at best.

To assess software security more objectively, ESG asked respondents whether their organization ever experienced a security incident directly related to the compromise of internally developed software. As it turns out, one-third of critical infrastructure organizations have experienced one or several security incidents that were directly related to the compromise of internally developed software (see Figure 18).

From an industry perspective, 39% of financial services firms have experienced a security incident directly related to the compromise of internally developed software compared with 30% of organizations from other critical infrastructure industries. This happens in spite of the fact that financial services tend to have advanced cybersecurity skills and adequate cybersecurity resources. ESG finds this data particularly troubling since a cyber-attack on a major U.S. bank could disrupt the domestic financial system, impact global markets, and cause massive consumer panic.

Critical infrastructure organizations recognize the risks associated with insecure software and are actively employing a variety of security controls and software assurance programs. The most popular of these is also the easiest to implement as 51% of the organizations surveyed have deployed application firewalls to block application-layer cyber-attacks such as SQL injections and cross-site scripting (XSS). In addition to deploying application firewalls, about half of the critical infrastructure organizations surveyed also include security testing tools as part of their software development processes, measuring their software security against publicly available standards, providing secure software development training to internal developers, and adopting secure software development lifecycle processes (see Figure 19). Of course, many organizations are engaged in several of these activities simultaneously in order to bolster the security of their homegrown software.

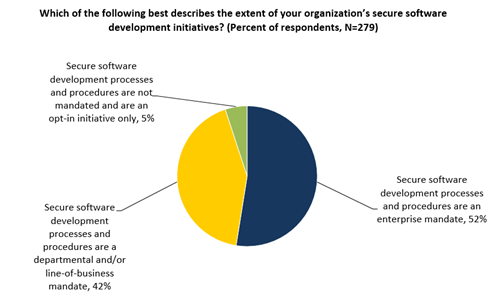

Secure software development programs are certainly a step in the right direction, but software assurance effectiveness is a function of two factors: the types of programs employed and the consistency of these programs. ESG research reveals that just over half of critical infrastructure organizations treat secure software development processes and procedures as an enterprise mandate, so it’s likely that these firms have a consistent secure software development methodology across the organization.

Alternatively, 42% of the critical infrastructure organizations surveyed implement secure software development processes and procedures as departmental or line-of-business mandates (see Figure 20). Decentralized software security processes like these can lead to tremendous variability where some departments institute strong software assurance programs while others do not. Furthermore, secure software development programs can vary throughout the enterprise where one department provides training and formal processes while another simply deploys an application firewall. As the old saying goes, “One bad apple can spoil the whole bunch”—a single department that deploys insecure internally developed software can open the door to damaging cyber-attacks that impact the entire enterprise and disrupt critical infrastructure services like food distribution, health care, or telecommunications.

Critical infrastructure organizations are implementing secure software development programs for a number of reasons, including adhering to general cybersecurity best practices (63%), meeting regulatory compliance mandates (55%), and even lowering costs by fixing software security bugs in the development process (see Figure 21).

It is also worth noting that 27% of critical infrastructure organizations are establishing secure software development programs in anticipation of new legislation. These organizations may be thinking in terms of the NIST cybersecurity framework (CSF) first introduced in February 2014. Although compliance with the CSF is voluntary today, it may evolve into a common risk management and regulatory compliance standard that supersedes other government and industry regulations like FISMA, GLBA, HIPAA, and PCI-DSS in the future. Furthermore, the CSF may also become a standard for benchmarking IT risk as part of cyber insurance underwriting and may be used to determine organizations’ insurance premiums. Given these possibilities, critical infrastructure organizations would be wise to consult the CSF, assess CSF recommendations for software security, and use the CSF to guide their software security processes and controls wherever possible.

Aside from the ongoing software security actions taken today, critical infrastructure organizations also have future plans—28% plan to include specific security testing tools as part of software development, 25% will add web application firewalls to their infrastructure, and 24% will hire developers and development managers with secure software development skills (see Figure 22). These ambitious plans indicate that CISOs recognize their software development security deficiencies and are taking precautions in order to mitigate risk.

Some software development, maintenance, and testing activities are often outsourced to third-party contractors and service providers. This is the case at half of the critical infrastructure organizations that participated in this ESG research survey (see Figure 23).

As part of these relationships, many critical infrastructure organizations place specific cybersecurity contractual requirements on third-party software development partners. For example, 43% mandate security testing as part of the acceptance process, 41% demand background checks on third-party software developers, and 41% review software development projects for security vulnerabilities (see Figure 24).

Cybersecurity, Critical Infrastructure Security Professionals, and the U.S. Federal Government

ESG research indicates a pattern of persistent cybersecurity incidents at U.S. critical infrastructure organizations over the past few years. Furthermore, security professionals working in critical infrastructure industries believe that the cyber-threat landscape is more dangerous today than it was two years ago.

To address these issues, President Obama and various other elected officials proposed several cybersecurity programs such as the NIST cybersecurity framework and an increase in threat intelligence sharing between critical infrastructure organizations and federal intelligence and law enforcement agencies. Of course, federal cybersecurity discussions are nothing new. Recognizing a national security vulnerability, President Clinton first addressed critical infrastructure protection (CIP) with Presidential Decision Directive 63 (PDD-63) in 1998. Soon thereafter, Deputy Defense Secretary John Hamre cautioned the U.S. Congress about CIP by warning of a potential “cyber Pearl Harbor.” Hamre stated that a devastating cyber-attack, “… is not going to be against Navy ships sitting in a Navy shipyard. It is going to be against commercial infrastructure.”

Security professionals working at critical infrastructure industries have been directly or indirectly engaged with U.S. Federal Government cybersecurity programs and initiatives through several Presidential administrations. Given this lengthy timeframe, ESG wondered whether these security professionals truly understood the U.S. government’s cybersecurity strategy. As seen in Figure 31, the results are mixed at best. One could easily conclude that the data resembles a normal curve where the majority of respondents believe that the U.S. government’s cybersecurity strategy is somewhat clear while the rest of the survey population is distributed between those who believe that the U.S. government’s cybersecurity strategy is very clear and those who say it is unclear.

ESG views the results somewhat differently. In spite of over 20 years of U.S. federal cybersecurity discussions, many security professionals remain unclear about what the government plans to do in this space. Clearly, the U.S. Federal Government needs to clarify its mission, its objectives, and its timeline with cybersecurity professionals to gain their trust and enlist their support for public/private programs.

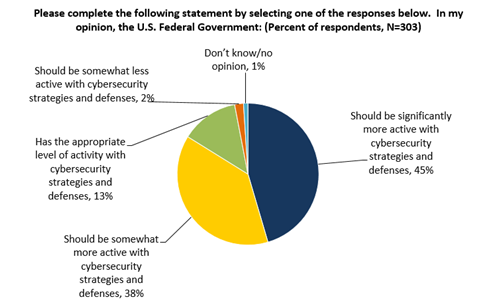

While critical infrastructure security professionals may be uncertain about the U.S. Federal Government’s strategy, they would also like to see Washington become more engaged. Nearly half (45%) of critical infrastructure organizations believe that the U.S. Federal Government should be significantly more active with cybersecurity strategies and defenses while 38% believe that the U.S. Federal Government should be somewhat more active with cybersecurity strategies and defenses (see Figure 32).

Finally, ESG asked the entire survey population of security professionals what types of cybersecurity actions the U.S. Federal Government should take. Nearly half (47%) believe that Washington should create better ways to share security information with the private sector. This aligns well with President Obama’s executive order urging companies to share cybersecurity threat information with the U.S. Federal Government and one another. Cybersecurity professionals have numerous other suggestions as well. Some of these could be considered government cybersecurity enticements. For example, 37% suggest more funding for cybersecurity education programs while 36% would like more incentives like tax breaks or matching funds for organizations that invest in cybersecurity. Alternatively, many cybersecurity professionals recommend more punitive or legislative measures—44% believe that the U.S. Federal Government should create a “black list” of vendors with poor product security (i.e., the cybersecurity equivalent of a scarlet letter), 40% say that the U.S. Federal Government should limit its IT purchasing to vendors that display a superior level of security, and 40% endorse more stringent regulations like PCI DSS or enacting laws with higher fines for data breaches (see Figure 33).

Of course, it’s unrealistic to expect draconian cybersecurity policies and regulations from Washington, but the ESG data presents a clear picture: Cybersecurity professionals would like to see the U.S. Federal Government use its visibility, influence, and purchasing power to produce cybersecurity “carrots” and “sticks.” In other words, Washington should be willing to reward IT vendors and critical infrastructure organizations that meet strong cybersecurity metrics and punish those that cannot adhere to this type of standard.

|

|